By PHUOC LE, MD, CONNIE CHAN, and BROOKE WARREN

I recently took care of Rosaria[1], a cheerful 60-year-old woman who came in for chronic joint pain. She grew up in rural Mexico, but came to the US thirty years ago to work in the strawberry fields of California. After examining her, I recommended a few blood tests and x-rays as next steps. “Lo siento pero no voy a tener seguro hasta el primavera — Sorry but I won’t have insurance again until the Spring.” Rosaria, who is a seasonal farmworker, told me she only gets access to health care during the strawberry season. Her medical care will have to wait, and in the meantime, her joints continue to deteriorate.

Migrant and seasonal agricultural workers (MSAW) are people who work “temporarily or seasonally in farm fields, orchards, canneries, plant nurseries, fish/seafood packing plants, and more.”[2] MSAW are more than temporary laborers, though— they are individuals and families who have time and time again helped the US in its greatest time of need. During WWI, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1917[3] because of the extreme shortage of US workers. This allowed farmers to bring about 73,000 Mexican workers into the US. During WWII, the US once again called upon Mexican laborers to fill the vacancies in the US workforce under the Bracero Program in 1943. Over the 23 years the Bracero Program was in place, the US employed 4.6 million Mexican laborers. Despite the US being indebted to the Mexican laborers, who helped the economy from collapsing in the gravest of times, the US deported 400,000 Mexican immigrants and Mexican-American citizens during the Great Depression.

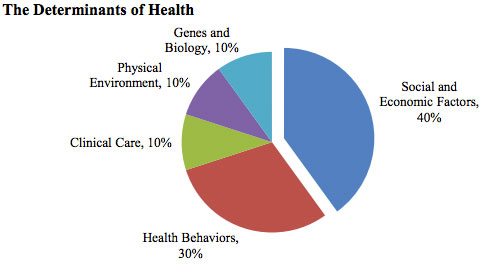

Today, there are about who live and work throughout the US, providing crucial labor for the US economy. Unfortunately, as with other exploited minority communities, MSAW have had to withstand from the effects of structural determinants which have ultimately led to poor health outcomes. In fact, 11.4% of MSAW infants versus 8.9% of non-MSAW infants are found to have perinatal medical conditions. This means MSAW infants are almost 30x more likely to experience perinatal medical conditions.

At the forefront of these structural determinants that determine health and wellness is economic stability. The average annual income of MSAW is between $15,000 to $17,499 per person and $20,000 to $24,99 per family. Workers are not paid per hour like many temporary jobs. Instead, they are “… often paid by the bucket; in some states they earn as little as 40 cents for a bucket of tomatoes or sweet potatoes.”[4] To earn $50, farmworkers need to pick about two tons of produce.

How can we tell patients to make their health a first priority when they are doing painstaking work that does not allow them to attain enough economic stability to provide for themselves and their families?

Although their livelihoods are dependent on the cultivation of food, many farmworkers, ironically, are food insecure. The reality that 59% of Indigenous farmworkers in Ventura, CA who said they did not have enough food for their families should give us pause.

Another structural determinant of health is dangerous work conditions. For example, pesticide drift exposure is hazardous for MSAW and their families. The relationship between exposure to pesticides on health outcomes in agricultural communities has been the focus of the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas study, a longitudinal cohort study run by the UC Berkeley School of Public Health.[5] The CHAMACOS found that “mothers who lived in close proximity to agricultural operations using the highest percentage of pesticides – the top 1 percent – had an 11 percent increased probability of preterm delivery and a 20 percent increased probability of having a low birthweight baby.”[6] The CHAMACOS study also found that living near farms is associated with respiratory problems in children. The youth who live in Salinas Valley’s agricultural community (a half-mile or less from pesticide application) have “…reduced lung function, more asthma-related symptoms, and higher asthma medication use…”[7] compared to unexposed children. This was found to be the direct result of organic farms using elemental sulfur to control fungal growth of crops and pests.[8]

Finally, access to healthcare is severely lacking for MSAW. . Twenty-two percent of farmworkers have an H2A visa (47% are unauthorized, 31% are US citizens)[9]Employers are not required to provide health insurance under the ACA for H2A because of their temporary status. The ACA only requires that employers let H2A recipients know of the health insurance options they can purchase themselves. California actually expanded federal Medicaid, allowing H2A workers who fall below 138% poverty level to qualify for Medicaid.

Many of these structural determinants impact MSAW patients well before they even step into the examination room. Even so, providers should assist in offering necessary care and advocacy for MSAW patients as well as make it a point to understand these structures in order to have context for conversations about care plans. Clinicians can help MSAW by supporting organizations like Farmworker Justice, Migrant Clinicians Network, and the National Center for Farmworker Health, Inc (NCFH) who work with, by, and for the MSAW community. Providers can join arms with organizations like these to advocate for migrant and seasonal agricultural workers who have been systematically oppressed by structural forces outside of their control. If we don’t, we will be jeopardizing the health of our patients, like Rosaria, whose health and livelihood are dependent on the current system that fails them.

[1] Name changed for patient confidentiality

[2] https://www.migrantclinician.org/issues/migrant-info/migrant.html

[3] Mexico was not included in migration restrictions that the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1917 set in place for Eastern European, Southern European, and Asian immigrants.

[4] https://saf-unite.org/content/united-states-farmworker-factsheet

[5] The cohort participants were primarily born into families of immigrant farmworkers.

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-preemies-pesticides/moms-most-exposed-to-pesticides-more-likely-to-have-preterm-babies-idUSKCN1BN2YC

[7] https://www.futurity.org/elemental-sulfur-children-1515012/

[8] Although elemental sulfur is found in our everyday food, when inhaled, it is results in poor respiratory outcomes.

[9] An H2A Visa given by agricultural employers who anticipate a shortage of domestic workers to bring non-immigrant foreign workers to the US to perform agricultural labor or services of a temporary or seasonal nature

Internist, Pediatrician, and Associate Professor at UCSF, Dr. Le is also the co-founder of two health equity organizations, the HEAL Initiative and Arc Health.

Connie Chan and Brooke Warren are currently interns at Arc Health. Chan is an Economics and Public Health double major and graduate of UC Berkeley. Warren is a Native American Studies major and recent graduate of UC Davis.

This post originally appeared on Arc Health here.

The post A System that Fails Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Workers appeared first on The Health Care Blog.