U.S. health care policies should be based on solid evidence, especially those policies with life-and-death consequences. All too often, though, they are not. Consider the recommendation by congressional advisors that the government should favor basic ambulances with only minimal equipment and less trained staff over advanced ambulances with more life-saving equipment and better trained staff. A poorly controlled study, however, claimed that patients were more likely to die during or after riding in the advanced ambulances than in the basic (but cheaper) ambulances.

Why would “basic” ambulances (with less life-saving equipment and with lesser trained staff) be better than the more advanced ambulances? They probably were not, and we’ll show how the data supporting the benefits of “basic” ambulances are unreliable, and often confuse cause and effect. Worse perhaps, the study offers yet another example of economic research devoid of context generating dubious national policy.

The Study

Researchers at the University of Chicago and Harvard Medical School used insurance data to examine how well a large sample of Medicare beneficiaries fared after ambulance transport for out-of-hospital emergencies. They compared those sent in basic life support ambulances vs. people transported in advanced life support ambulances.

The results, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, are of course counterintuitive: patients transported to the hospital in Advanced Life Support ambulances were more likely to die than those riding in the simpler, basic ambulances.

Questioning the Study’s Continuing Impact

The study is continuing to reverberate in research and policy circles. Almost a year after its publication, it was vigorously debated at the prestigious conference of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP). Most emergency medicine leaders there questioned the veracity of the study and wondered about the absence of collaboration with emergency medicine specialists, who are trained in ambulance dispatch decisions that match the severely ill or dying patients with the most effective emergency transport. The emergency physicians also expressed worry that Medicare might reduce reimbursement for advanced ambulances on the basis of this unreliable study.

More troubling, in an recent interview , one national expert, Dr. Howard Mell, worried that the study represented a “ticking time bomb” (personal communication) given the new president’s emphasis on cuts to health care.

Most severely ill Medicare patients are currently transported by advanced life support ambulances, so it would be great if the cheaper ones were better. But there are several reasons why it’s premature for policymakers to act on this finding—yet another untrustworthy study with poor research methods, but much media hype.

The Evidence: Confusing Cause and Effect

First, the study seems to assume that severely ill patients are assigned to either an advanced or a basic ambulance by the flip of a coin. But this is not the case. Policy demands that advanced ambulances are sent to sicker patients, those further from the hospital and those more likely to die on route. It’s not random selection (like gold standard randomized trials); it’s often carefully considered selection.

Second, the study is almost devoid of data on how sick the patients were in each type of ambulance—exactly the sort of information emergency services often consider in assigning advanced life support ambulances in an effort to save critically ill patients.

This study wrongly creates the impression that advanced ambulances cause more deaths. In fact, they transport patients who are already more likely to die.

One large study shows that advanced ambulance teams are twice as likely as basic ambulances to pick up people with respiratory distress, serious breathing conditions, resulting in more deaths. In other words, people who are barely breathing are 100% more likely to get more advanced ambulances, making it appear that advanced ambulances “cause” more deaths when it is the opposite. People who can’t breathe and are more likely to die, are sent advanced ambulances in efforts to save their lives (the very definition of triage).

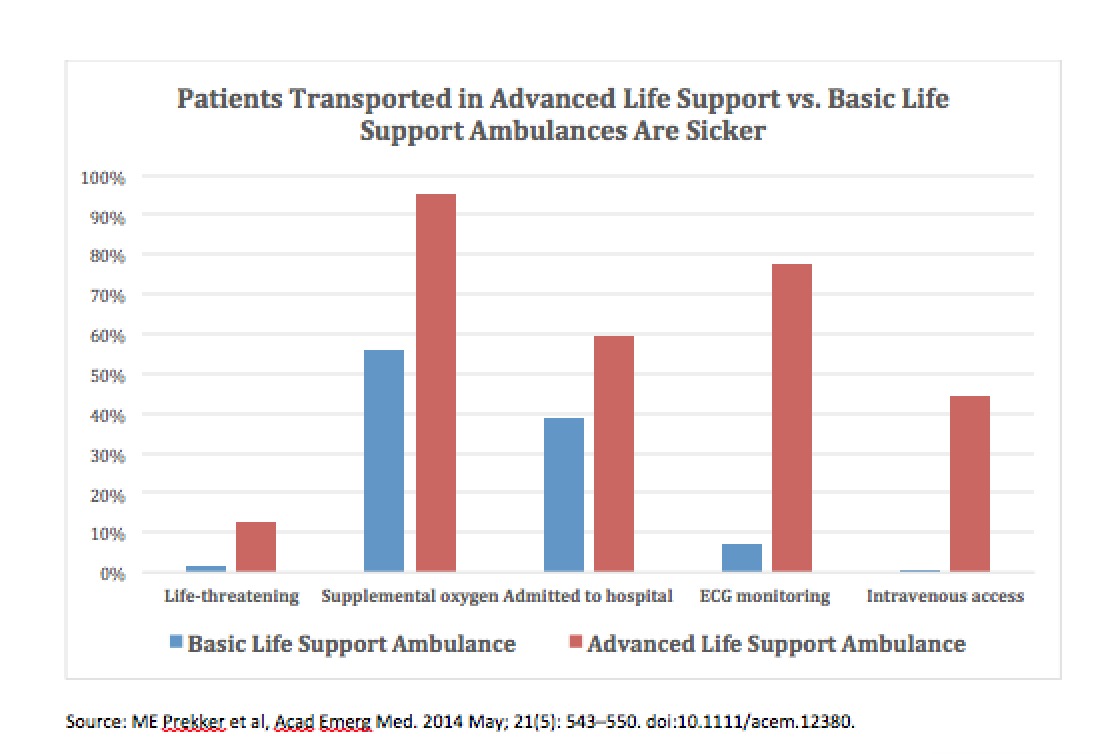

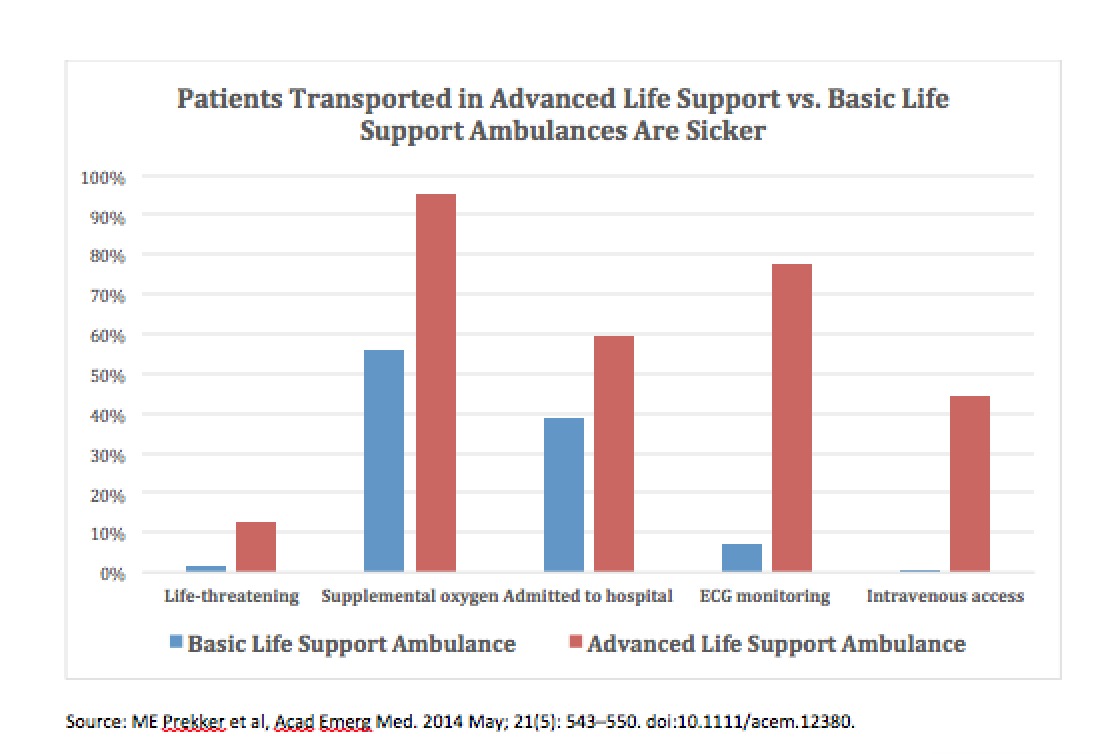

As can be seen in the above figure, patients transported in advanced ambulances were far more likely to be suffering life-threatening conditions. They were almost twice as likely to have supplemental oxygen, were a third more likely to be admitted to the hospital, and had 12 times the rate of electrocardiograph monitoring. Moreover, only patients in the advanced support ambulances had intravenous lines.

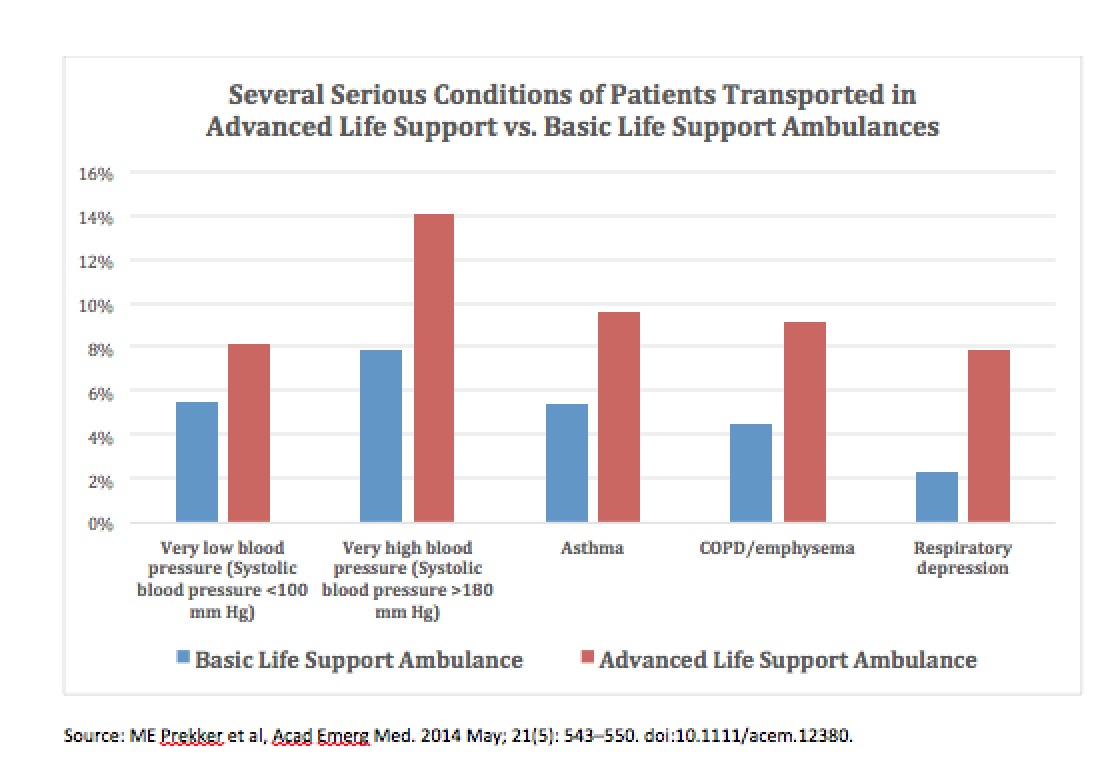

The graph above, likewise illustrates the more severe clinical conditions of patients transported in advanced ambulances. They were a fifth more likely to have very low blood pressure, and a third more likely to have very high blood pressure. They were almost twice as likely to have asthma or emphysema, and almost four times more likely to suffer from respiratory depression.

This is hardly the result of a flip of the coin. Remember also, all of these conditions occurred before hospitalization. All of the advanced ambulance patients were more likely to die from a large number of severe conditions occurring at the time they were picked up. It is virtually impossible to state that the health of patients transported by basic and advanced life support ambulances were the same.

What’s more, basic ambulances are more likely to pick up patients from skilled nursing facilities, where they are used as taxis to move healthy elderly to routine medical procedures—not usually near-death events.

Yet, another problem with the study is that it is correlational: research comparing patients during the same period of time. There is no calculation of any change in (or “effect” on) deaths. This type of design is so weak that the international scientific body that reviews tens of thousands of medical studies (Cochrane) immediately rejects it as evidence—even before examining any other weaknesses.

Not surprisingly, in an online forum, emergency medical technicians who attempt to resuscitate seriously ill patients reacted skeptically to the study’s findings.

One EMT responded, “We don’t send basic life support ambulance to a head-on car crash on a freeway.”

Another stated, “A basic unit probably won’t be activated for an elderly person who’s difficult to arouse, complaining of chest pain.”

And another: “… if you are receiving an advanced life support ambulance from the start, it is because the dispatch center infers your situation is severe enough to require ALS [an advanced life support] ambulance. So you are already more likely to experience poorer outcomes if you are being sent an ALS [the advanced life support] ambulance.”

Despite these limitations, the article’s authors proclaimed the salutary implications of their study, even calculating that the country would save many millions by abandoning more expensive advanced ambulances.

And, as usual, media outlets, including the Washington Post, trumpeted the findings under exaggerated headlines: “Need an ambulance? Why you might not want the more sophisticated version.”

Health policies with life-and-death consequences deserve strong evidence. At present, too much of the research in this field is weak. The National Institutes of Health have identified a disturbing phenomenon, the non-reproducibility of science. Unreliable studies confuse doctors, scientists, local politicians, and policymakers. They can also harm patients. Less expensive medical care is sometimes more effective, wise and more humane. But if the federal government overgeneralizes that message from unreliable studies on emergency care, we may see fewer patients survive their journeys to the hospital. More generally, we must not let weak research dictate policy that appears to be politically attractive but is foolish or harmful.

Stephen Soumerai is Professor of Population Medicine and teaches research methods at Harvard Medical School and the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute.

Professor Ross Koppel teaches research methods and statistics in the Sociology department at the University of Pennsylvania and is a Senior Fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute (Wharton) of Health Economics. He is also affiliate professor of medicine at Penn’s medical school