By ANISH KOKA, MD

No one likes getting bills. But there is something that stinks particularly spectacularly about bills for healthcare that arrive despite carrying health insurance. Patients pay frequently expensive monthly premiums with the expectation that their insurance company will be there for them when illness befalls them.

But the problem being experienced by an

increasing number of patients is going to a covered (in-network) facility for

medical care, and being seen by an out-of-network physician. This happens because

not all physicians working in hospitals serve the same master, and thus may not

all have agreed to the in-network rate offered by an insurance company.

This is a common occurrence in medicine.

At any given time, your local tax exempt non-profit hospital is out of network

of some low paying Medicaid plan or the other.

In this complex dance involving patients, insurers and doctors, Patients want their medical bills paid through premiums that they hope to be as low as possible, Insurers seek to pay out as little of the premium dollars collected as possible, and Doctors want to be paid a wage they feel is commensurate to their training and accumulated debt.

Insurers act as proxies for patients when

negotiating with the people that actually deliver healthcare – doctors.

Largely, the system works to funnel patients to ‘covered’ doctors and

hospitals. Patients that walk into an uncovered facility are quickly

redirected. But breakdowns happen during emergencies.

There are no choices to make for patients

arriving unconscious or in distress to an emergency room. It suddenly becomes

very possible to be seen by an out of network physician, and depending on the

fine print of the insurance plans selected some or none of these charges may be

covered.

Physicians that typically prefer banal

chants of “health is care for all” and avoid deep dives into policies

that determine physician reimbursement may want to pay attention to the debate

because it provides a clear picture of the forces currently trying to shape the

conversation about how to value physicians. The news is not good.

Practically speaking, no physician wants the hassle of being out of network. Ethically, few physicians have the stomach for bankrupting patients, and attempting to collect from the uninsured isn’t a desirable brand to cultivate. For those patients left with a balance, its actually illegal on the part of physicians to not attempt to collect. On the inevitable non-receipt of the balance, steep discounts or a write-off follows. So despite the heated rhetoric surrounding physicians ‘fleecing’ patients, the amount of real dollars collected from patients is never mentioned. While this number is hard to ascertain, a good proxy may be medical bankruptcies, which is a relatively rare event. So the amount of smoke that has been generated from, what in absolute terms, is a small fire has little do with patients and everything to do with how we figure out what to pay physicians.

The traditional leverage physicians have employed against insurers is the ability to not accept rates offered by payers. This isn’t unusual – its fundamental to every negotiation between two parties where the laborer isn’t conscripted. A mango seller has a price below which he won’t sell mangos. The negotiation would go much differently if the mango seller was compelled to sell his mangos at some price. The problem for insurers is that the pressure from patients to have in-network doctors is intense. Patients pay steep monthly premiums so they won’t get large, potentially bankrupting health care bills when they need medical care. And so the ability of physicians to not accept a proffered rate is fundamental to the negotiation between insurer and physician. The threat of a doctor being out of network raises the in-network rates. The threat of not getting a mango belie a certain price raises the price of the mango. Not complicated.

Further more, physicians that deliver services during emergencies – anesthesiologists, ER physicians, orthopedic trauma, neurosurgery – have greater leverage than physicians who don’t deliver emergency care. Insurers are far more effective at negotiating with primary care physicians because a primary care physician who chooses not to accept the contract of a certain insurer effectively shuts themselves out of that network. Insurers have no such luck directing patients in times of emergencies. The demand for services in this context is ‘inelastic’, giving physicians significant latitude in negotiating contracts with insurers. This is a giant thorn in the side of insurance companies that complain high medical premiums are a direct result of the high prices they must pay for these services.

‘High’, of course, is a relative term. They think of the rates they pay relative to the rates Medicare pays. Medicare enjoys one of a kind leverage because it is a legislatively created behemoth consolidating the buying power of the entire over 65 population under a government administered and enforced program. That leverage means Medicare rates are significantly lower than private rates, and specialties with greater inelastic demand are able to extract significant multiples of Medicare rates.

Insurance companies would like nothing

more than legislative help that would limit the amount they have to pay

physicians. Their ally in this fight is the simple fact that health care isn’t

quite like selling mangoes. In the healthcare marketplace, vulnerable patients

arrive in emergency departments in extremis with little ability to make choices,

and so many argue this is the very place the government needs to protect

hapless citizens.

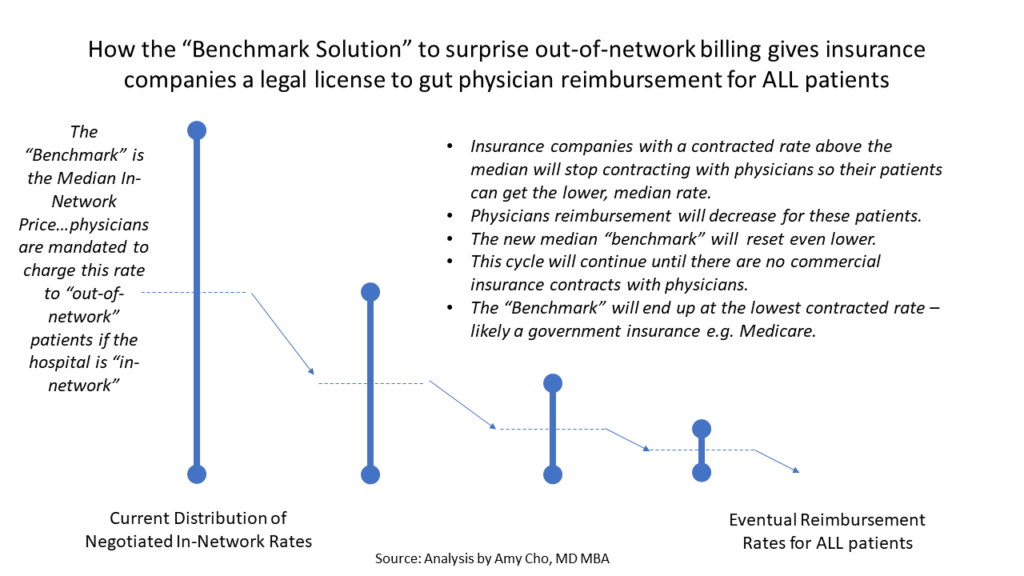

The solutions that comes from health

policy/economists is also endorsed by the Senate Health, Education, Labor and

Pensions committee (HELP). This bipartisan group supports federally benchmarked

caps on rates that can be charged that are pegged to the median (50%)

in-network rate for an area. So if a patient happens to be seen by a physician

that is out of network, the insurer would pay the median in-network rate in the

area. But in this plan, there would be no incentive going forward for insurers

who contract at higher than the median in-network rates to stay in-network.

What would be the point? Just drop the contract, since the out of network rate

gets you 50% of the area in-network rates. This creates a race to the bottom

that effects reimbursement rates for all patients.

Figure courtesy of @amychomd

Physicians in practice and in congress

favor a different approach to get patients out of the line of fire: Independent

Dispute Resolution (IDR). The IDR, implemented in New York City in 2015, seeks

to take patients out of the middle by sending disputes between providers and

insurance to binding arbitration. Generally, the effect is that providers and

insurers settle disputes between themselves before a third party gets involved.

The desire to avoid potential third party arbitration also has the effect of

increasing in-network rates. This isn’t theory. The New York legislation

increased in-network provider participation, saved patients money, and lowered

in-network physician rates.

Interestingly, the health policy

community has taken the tack of rejecting the physician endorsed solution, and

accusing supporters in the provider community as greedy shills interested in

profits over patients. A frequently raised point is the fact that some Private

Equity firms own ER groups and are lobbying for IDR and against median

benchmarking. Apparently, any policy that would result in Private Equity

profiting is a bridge too far for the policy community. It goes unmentioned

that in the battle between insurers and doctors, the health policy community

places itself squarely on the side of health insurance company profits.

There is also remarkably little

appreciation for the second order effects of decreasing reimbursement to

physicians expected to be ready for emergencies. The vessel that bursts in your

brain requires a team acting quickly to recognize and treat this emergency.

Will neurosurgeons, anesthesiologists , and emergency medicine physicians of

quality be available at 2 am? Neurosurgeons are likely to choose to avoid being

on call, and recommend transferring patients to facilities with the scale and

infrastructure to keep Neurosurgeons on call for emergencies. Transfers to quaternary

care facilities take time. Time is brain. The amount of brain damage is the

difference between slight weakness of that right hand grip while drinking a

glass of wine at home or a dense paralysis of the entire right half of your

body that translates to a nursing home and a feeding tube. The potential downsides of policy that

reduces reimbursement to a highly specialized group and thus could reduce

access are not small, but seem to be underappreciated by policy ‘experts’

bending the ear of members of Congress.

Policy experts are experts not because

they have any experience trying to manage and run a physician practice, but

because they are lords of the empiricism found in the peer reviewed literature

of the day. For some reason this puts

them on a level playing field with the people who run practices and have to

meet payroll every 2 weeks. Its certainly possible the process of running a

business is entirely too narrow a field of view, but its unclear that the

policy experts field of view is more enlightening.

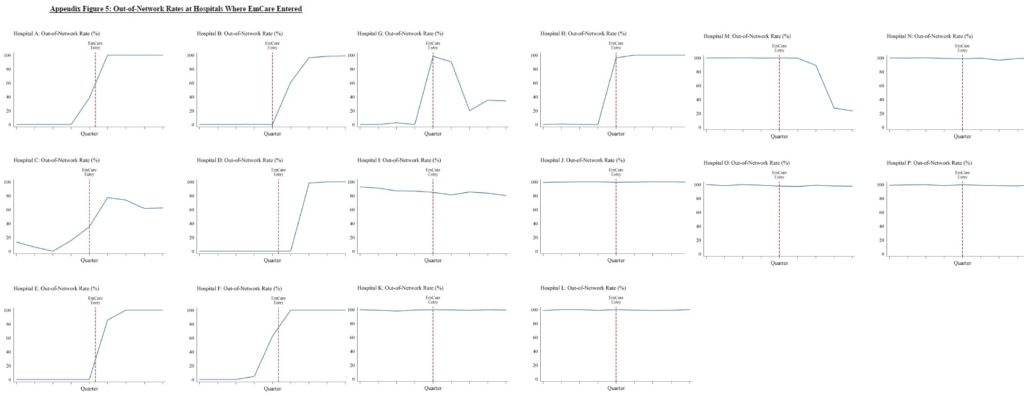

Zach Cooper at Yale has done a lot of work in this space, and one of his papers that is cited often is derived from claims data provided by a large private insurer. The general hypothesis of the study is that large profit hungry private firms that own ER practices flung across the nation engage in predatory activity once they acquire a local ER group. This ultimately raises costs to the patient, and thus damages societal welfare as a whole. Using the company websites of the private firms, the researchers were able to divine that the two companies (TeamHealth and EMcare) were involved in a whopping 9% of their national sample. In order to understand how the entry of these firms may impact medical charges and reimbursement, the investigators found a total of 26 hospitals the firms initiated contracts with in the time frame studied.

The authors divine many thing from the

raw data. To support the claim that arrival of the private groups may have

increased out of network rates to fleece patients and improve their leverage

for in-network rates the authors examine the data and conclude: “In Panel

A of Figure 3, the raw data show a clear increase in out-of-network billing

rates at hospitals immediately after EmCare entered.” The strange thing, however, is that the raw

data of the 16 hospitals there was data on that looked at OON rates after EM

health enters a market, shows a clear temporal association of rates rising

after EM health arrived in only 2 cases. In 4 hospitals, OON rates started to

rise before EM health entered, and in the remaining cases, OON rates were

either unchanged, or were seen to decrease.

The authors proceed to firmer footing

when they discuss the charges billed, because the insurer they are working with

has been nice enough to provide this information for every patient they

received a charge for. They find that the entry of EMcare increases charges by

$556.84 (96%). They note that some of this increase occurred because the

intensity of coding that reflects how sick the patient is increased significantly

soon after EMcare enters. The implication, of course, is made that this

upcoding is improper, yet no support is provided for that assertion. It is just

as plausible that physicians were

undercoding the severity of patients prior to EMcare entering the market – this

narrative defying possibility goes unmentioned.

The absolute amounts being discussed also

bears attention. The OON payments that

were paid by insurers after EMcare entered the market increased by $402.67.

Patient cost sharing payments increased by $45. Now it is possible that

patients may have balances beyond these paid charges, but even this amount

comes to $195. These averages paid here exclude ~ 217,000 claims where insurers

paid nothing because of a claim denial.

These numbers aren’t zero, but for emergency medical care, these numbers

($195+ $45) are still far south of the average apple watch.

The most vulnerable patients of course,

don’t have health insurance, and aren’t buying apple watches. For this group, the total potential liability

could range from $578 to $1135. It

isn’t known what is actually collected from this group of patients as the

administrative costs of trying to collect in this population are not small, and

there is most certainly a reputational cost to bear in the community for

generating these bills.

The underlying assumption that runs

through the paper is that the price being paid for these services is too high

because patients are unable to shop for care in an emergency. But this ignores the fact that in our

current system, its the insurance company that acts as an agent for the

patient. They are well aware when they

sign patients up for a health care plan that an out-of-network may happen. So while much of the focus in this debate is

on the bill generating providers, one wonders how it came to be that that

insurance plans are allowed to sell plans to patients that don’t offer any out

of network coverage. Should a facility

be considered in-network if physicians that work at the facility are out of

network? Shouldn’t patients be informed of this by their insurance company? The

insurance company is fully aware of the consequences – so why is the bill that

passes through to patients a surprise? The only party with foreknowledge of

what may happen is the insurance company.

They have every ability to shop on the marketplace, and it is their

failure to secure a contract and then communicate this to their customers that

results in ‘surprise’ bills.

In order to buttress the idea of ‘high’

cost, the paper attempts to use reference Medicare payments. Its noted that Internists are paid 158% of

Medicare rates, orthopedists 266% of Medicare rates while the rates paid to the

2 ER firms in the paper are 364% and 536% of Medicare rates. It only serves passing mention that the

average amounts paid exclude 217,000 claims where nothing was paid because the claim was denied. There is also no mention made of the

difference between elective care provided by orthopedists and internists versus

the almost entirely emergent care provided by ER physicians that is delivered

without consideration of the patients ability to pay. ER physicians are legally (because of a law

called EMTALA) and ethically bound to take care of patients who arrive in the

ER in distress. This means they shoulder

a far heavier responsibility for uninsured care than almost any other

specialty. Most physicians who deliver

care in the outpatient setting require a payment arrangement be made prior to

seeing a patient. The ER physician has

no such recourse. Not mentioning this

when discussing rates paid to ER physicians, and other physicians delivering

care in emergencies is a feat of obfuscation and deception.

The researchers and other commentariat

from the policy community also seem to fail at understanding the motivations of

doctors in the current system. I can think of no physicians that want patients

getting these bills. In the current

third party payer system, opacity is the physicians friend. Given the reputational cost, and the

administrative cost of trying to collect these bills, physicians more so than

policy wonks are highly motivated for a solution that takes patients out of the

mix and generally endorse the previously mentioned third party arbitration

system.

This is reluctantly analyzed by Cooper

et. al., as well. Implemented in New

York in 2014, the study finds that the OON rate went from 20% in 2013 to 6% in

2015. Unimpressed, the authors dismiss

the solution as being “administratively complex and potentially

costly” because it requires patients to know about, and fill out a one

page form if they were to receive a bill.

This ‘analysis’ misses the fundamental point that IDR results in a huge

drop in the chance these bills are being sent to patients, or that most

disputes are resolved without even involving the IDR.

One is struck by the hubris of the

inevitable conclusions the researchers arrive at based on data provided from

one insurer and an analysis of 2 firms. As noted previously, the raw data

consists of a small handful of hospitals from this already small sample, and

doesn’t even tightly demonstrate the relationship of price to firm entry. Even

if we assume prices rise, the conclusion that consolidation raises prices.

Water, I’m told, is also wet. No data is provided on changes to the local

marketplaces in this small sample during the time studied. Profit seeking is

certainly one plausible explanation, but its also just as possible that a

greater proportion of underinsured or poorly insured patients arriving in the

ER during the same time was responsible for raised rates. Apparently the policy

memory is amnestic to The Dartmouth institute that changed the landscape of

healthcare policy with its reports of regional variation Medicare spending. The

small problem was that this dataset didn’t take into account private insurance

spending. Subsequent publication of data from the economists the insurance

industry uses (Cooper et. al) invalidated the Dartmouth data. Context matters.

So this battle has little to do with

patients. The rejection of the IDR in

favor of an untested proposal physicians don’t endorse is part of an

ideological battle waged by a group of folks that have decided health care is

too expensive (it is) and that physicians need to be devalued to create a

better system. Data to support this

ideology conveniently comes from those with an outsize interest in paying less

for physician labor: the insurance industry that pays for healthcare in our

current system. Given that the only data

the insurance companies really have is the amount that they pay for services

rendered, it should perhaps come as little surprise the conclusions draw from

this data is as weak as it. Importantly, this data has little bearing on what

the right price for these services are, what the best mechanism to get the

right price is, or what the downsides of untried, untested policies are.

There is a real argument worth having

about health care prices and how they can be lowered. A number of regulatory

straitjackets harm competition and creates a landscape of large players that

have kept prices high. Sitting inside the guts of the healthcare system, it is

easy to see rent seekers in every health care sector that proliferate.

Physicians aren’t entirely blameless, and a better more efficient may very well

see many physicians making less, but it would be wise to act more like the

skilled surgeon rather than the butcher to avoid killing the patient.

Anish Koka is a cardiologist in practice in Philadelphia.

The post Guerilla Billing – Missing the Gorilla in the Midst appeared first on The Health Care Blog.