By SAURABH JHA, MD

“There are some enterprises in which a careful disorderliness is the true method” – Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Asymmetry of Error

During the Ebola epidemic calls to ban flights from Africa from some quarters were met by accusations of racism from other quarters. Experts claimed that Americans were at greater risk of dying from cancer than Ebola, and if they must fret they should fret more about cancer than Ebola. One expert, with a straight Gaussian face, went as far as saying that even hospitals were more dangerous than Ebola. Pop science reached an unprecedented fizz.

Trader and mathematician, Nassim Taleb scoffed at these claims. Comparing the risk of dying from cancer to Ebola was flawed, he said, because the numerator and denominator of cancer don’t change dramatically moment to moment. But if you make an error estimating the risk of Ebola, the error will be exponential, not arithmetic, because once Ebola gets going, the changing numerator and denominator of risk makes a mockery of the original calculations.

The fear of Ebola, claimed Taleb, far from being irrational, was reasonable and it was its comparison to death from cancer and vending machines which was irrational and simplistic. Skepticism of Ebola’s impact in the U.S. was grounded in naïve empiricism – one which pretends that the risk of tail events is computable.

The U.S. got away lightly with Ebola. It would seem the experts had rebutted Taleb. But the experts were wrong, in fact wronger than wrong, despite being right. To understand why you need to invoke second order thinking. Their error was in failing to appreciate the asymmetry of error. Error is often unequal. The error from underestimating Ebola is magnitudes higher than the error from overestimating its impact. Their error lay in dismissing counterfactuals. Counterfactuals eventually catch up with you.

Imagine you’re hiking in the Mojave desert, which is rattlesnake territory, and a billionaire pays you $10 for lifting rocks. There’s a chance you could blindly lift rocks without being bitten by a rattlesnake. But the error is asymmetric because the pay off, the outcome, is asymmetric. If you don’t lift the rock, wrongly believing there is a rattlesnake underneath it, you forfeit $10. If you lift the rock, wrongly believing there’s no rattlesnake underneath it, you will be dead. My guess is you will ignore the point estimate and confidence interval of “risk of rattlesnake underneath rock” and not lift rocks blindly.

A “2 % chance of being wrong” is meaningless without knowing what the consequences of being wrong are. A “0.1 % chance of a catastrophic event” is meaningless without acknowledging the error in that point estimate. Some events are so catastrophic that they render both point estimates and their range meaningless.

Tailgating in Extremistan

I found Taleb by chance. My train to New York was late. This was before Twitter, when I still read books, so I went inside the bookshop. I choose books randomly. I bought The Black Swan because the title sounded intriguing. At some point I came across this sentence “…the government-sponsored institution Fanny Mae when I look at their risks, seems to be sitting on a barrel of dynamite, vulnerable to the slightest hiccup.” I realized its significance six months later when Lehman Brothers collapsed, triggering the financial collapse of 2008. I had a “where have I seen you before” moment. I re-read The Black Swan. Taleb had predicted the financial collapse.

After the financial collapse, the prediction merchants, who were conspicuous by their absence during the rise of sub prime mortgages, came out of the woodwork in droves and eloquently explained why the financial collapse was inevitable. Explaining “why” after the event is much easier than explaining “how” before the event, and is a pretense of knowledge. Taleb takes apart our pretensions.

The ancient Greeks looked at the sky, joined the dots and told fascinating tales. Today we ask about the dietary and reading habits of people who have lucked out from the cosmic Monte Carlo simulator. Ten steps to becoming a millionaire are often ten steps to losing a million. The unsung loser, the denominator, is lost to publication bias.

Physicians are also prone to being fooled by randomness. We give a cluster of cases an eponym because we don’t understand chance. Autism’s fallacious link with the MMR vaccine is because we can’t get ourselves to say that bad things happen to good people for no body’s fault.

“Reflection is an action of the mind whereby we obtain a clearer view of our relation to the things of yesterday and are able to avoid the perils that we shall not again encounter,” the satirist, Ambrose Bierce, quipped. An entire industry thrives from our failure to appreciate chance. The industry retrospectively analyzes the event and, with hindsight, sees the problem with even greater clarity. Instead of being humbled, our belief in our predictive, preemptive and preventive powers becomes stronger.

In The Black Swan, Taleb uses the problem of induction as a metaphor for the unquantifiable. Even after seeing thousand white swans the statement “all swans are white” would be an epistemic error, disproven by a single black swan. Einstein put it similarly: “no amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment will prove me wrong.”

The world is shaped not by Gaussian laws but outliers. Taleb divides the world in to “mediocristan” and “extremistan.” Mediocristan is bell-shaped, loved by statisticians, predictable, with a tail that is inconsequential. Extremistan is dominated by a single event – the pay offs are large, meaning the tails are fat. Extremistan is unpredictable and consequential.

Book sales are in extremistan. Bill Gates is a product of extremistan. Physician incomes, as extreme as they may appear, are in mediocristan. Black swans rule extremistan and change the world. September 11th, 2001 was a black swan event, as was the collapse of the financial sector. We live in an interdependent world which is more prone than ever to black swans.

Taleb scorns at experts, particularly in the prediction industry, who he says suffer from the Ludic Fallacy. This is when we think we know the variable, or its distribution, used to derive risk. We confuse risks (known unknowns) and uncertainty (unknown unknowns). Experts are most wrong when it matters the most. The possible gives the probable, and the experts, a thorough hiding.

Fragile systems and Antifragility

Was Taleb lucky or prophetic in predicting the sub prime mortgage crisis? Perhaps neither. He was commenting on the fragility of the system, the subject of his book, Antifragile.

Fragile systems collapse under stress. The opposite of fragile is robust – a system unaffected by stress. Robust systems do not improve. Antifragile systems gain from stress. Antifragile is a neologism coined by Taleb. Nature is antifragile. Hormesis, the long terms gains of the body from small stressors, is a recognized biological phenomenon which illustrates antifragility. The stresses in antifragile systems are like a live attenuated vaccine which protects the body from its more virulent counterpart.

Black swan events can’t be predicted. But systems can be made less prone to outliers. According to Taleb, we should focus on pay-offs, not probabilities; exposure, not risk; mitigation, not prediction. Antifragile is Taleb’s peace offering – an epistemological middle ground where the unknowable compromises with our need to act. The fault lies not in our failure to predict Tsunamis, but in failing to make systems Tsunami proof.

The greatest strength of Antifragile is its domain independence. When read thoughtfully, its relevance to medicine, and evidence-based medicine, becomes clear.

Burden of proof in non linear systems

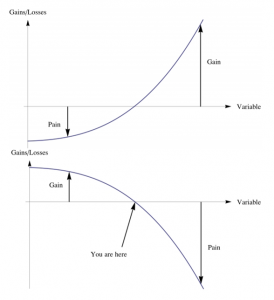

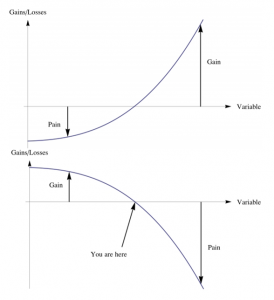

To understand fragility and antifragility you need to understand non-linearity which, despite the formidable mathematics, is easy intuiting.

The assumption that biological systems are linear may be fundamentally wrong. Biological systems are more likely a continuum between concave and convex functions. When f (x) is concave, the harm from an increment of ‘x’ is more than the gain from a decrement of ‘x.’ This is why less is sometimes more, why the quixotic search for pre-syndromic syndromes, overdiagnosis, can lead to net harm.

When f (x) is convex, not only more is more, but the gain from an increment of ‘x’ is more than that forfeited from a decrement of ‘x.’ In this zone indecisiveness has opportunity costs. If a patient is exanguinating, you must act, not look up Pubmed, even if you forfeit the most optimal action.

The line between the two domains is not precise. In medicine, convex and concave are often separable only by scale. For example, severe hypertension is convex, but mild hypertension is a concave function. Treating acute myocardial infarction, acute stroke, transplant rejection, and bacterial meningitis are convex functions. Secondary prevention is more convex than primary prevention. Antibiotics for common cold is concavity on steroids.

The twin dogmas of linearity are extrapolation and projection, which lead to errors in non linear systems. Projection, that is assumption a system, f (x), responds ten times at x = 100 as it does at x = 10, underestimates the response at x = 100. The small and uncertain benefits of stenting distal circumflex narrowing in chronic stable angina can’t be transported to left main lesions, which have a different degree of convexity.

Extrapolation, that is assumption that a system, f (x), responds one-tenth at x = 10 as it does at x = 100, overestimates the response at x = 10. The large and certain benefits of stenting proximal left anterior descending artery narrowing in ST-elevation myocardial infarction can’t be transported to distal circumflex lesions in chronic stable angina.

The convexity, or concavity, determines the burden of proof. Naïve empiricists err by assuming a constant burden of proof. The burden of proof for a screening test should be much higher than the burden of proof for a treatment of obstructive left main disease – think asymmetry of error.

The burden of proof ought to be highest when making policy decisions, when developing guidelines, when dictating standards, because if these have errors, conformity scales the error. An example was the conventional wisdom, and policy, which addressed pain control, and introduced “pain is the fifth vital sign” in physicians’ cognition. The error amplified exponentially when opioid analgesia was prescribed without compunction, leading to the intractable opioid crisis.

The challenge in medicine is fine tuning the burden of proof according to the asymmetry of error – a singular failure of evidence-based medicine which seems unable to display epistemic nuance.

Skin in the Game

Taleb has special respect for doctors. He doesn’t call people with PhDs “doctors.” He only calls MDs “doctors.” The respect is rooted in Taleb’s respect for the opinion of people who have “skin in the game.” If you have skin in the game you’re more likely to draw on your local knowledge, use what is important and discard what is irrelevant. To practice is to preach. But not everything that is relevant is articulated and much that is articulated is irrelevant.

I once attended a quality and safety talk where the speaker said “what cannot be measured cannot be improved. Measure, measure, measure!” Taleb might have recoiled at the epizeuxis and might have introduced the speaker to the “green lumber fallacy.”

The “green lumber fallacy”, coined by Taleb, is named after a trader in green lumber who thought green lumber was literally green, but it is so named because of its freshness, not color. However, this ignorance did not affect his trade. Experts make this fallacy when they mistake the visibility of knowledge for its necessity, and ignore hidden knowledge.

The tendency to dismiss the unknowable or unmeasurable was also described by Robert McNamara. The McNamara fallacy progressively disregards the intangible, that which does not appear extant to the quantifier. First we measure what we can. Then we assign what can’t be measured an arbitrary value. Then we disregard the unquantifiable as unimportant. Finally, we pretend the unquantifiable doesn’t exist. The transparency movement in healthcare may fall prey to McNamara fallacy by mistaking what is disclosed for what is relevant. The sauce may always remain secret.

There is a tension in health policy between the quants and the doctors in the trenches because the experts dismiss the doctors in the trenches, doctors who have skin in the game. Aggregation has become so fashionable that now the expected value, the mean, the net benefits reign, and the signal from variability, from outliers, is ignored. What works in Boston is expected to work in the Appalachia. Technocrats can be more valuable if they modified their models to fit reality. If they wish to preach to those who practice, they must consult the practitioners to whom they wish to preach.

For example, the history of the electronic health record (EHR) could have been different if its developers had paid more heed to the needs of the foot soldiers, the doctors and nurses, rather than the wants of regulators, payers, researchers, dreamers and other utopians. The technology has ended up in a developmental cul-de-sac, where it can’t get better without getting worse.

Optimizing Economies of Scale

Taleb takes apart healthcare’s two most sacred cows – optimization and economies of scale.

Taleb cautions against efficiency or optimization. In an optimized healthcare system – a health economist’s wet dream – all of healthcare is firing on all cylinders all the time delivering the highest quality-adjusted life years for the dollar. Efficiency is flying too close to the wind. Efficiency makes the system more fragile because efficient systems are usually efficient under normal conditions and not so efficient under abnormal stresses. Systems should have redundancies built in them. Perhaps healthcare should incentivize doctors to procrastinate, occasionally, rather than be hamsters on the productivity wheel.

In illustrating how economies of scale could become disasters of even larger scale Taleb hypothesizes what would happen if elephants were pets. When times are good the elephant’s share of the household budget is barely noticeable. During thrift, a “squeeze”, the maintenance costs for the elephant rise disproportionately and irreversibly, much more than they would for a cat.

The obvious elephant in our room is the EHR – healthcare’s very own Fukushima. The larger and more centralized EHR becomes, the costlier it will be to fix errors and privacy leaks; and one will have no choice but to fix them when they occur. The failure of interoperability may, paradoxically, spare us from a larger disaster.

By fiat or necessity hospitals are concatenating. The economies of scale which come with integration make the “Cheesecake Factory” model of healthcare appealing. But as alluded, elephants are more expensive to maintain than cats, particularly during thrift. Are we setting ourselves up for a supernova when healthcare becomes a red giant?

Complex Systems

Taleb reserves special derision for academic experts whom he calls “fragilistas”, or designers of fragile systems. I’m an academic, though far from an expert at anything. It’d be a mistake dismissing Taleb just because he doesn’t suffer fools gladly. Friederich Hayek opposed central planning because knowledge is too dispersed for the technocrat to know it all. Taleb cautions against too much planning because it interferes with organic growth.

Is our approach in healthcare fundamentally incorrect? After reading Antifragile, I believe so. In the narrative in healthcare, there’s an inordinate love for uniformity and standardization and an uncanny disdain for variability. For unbeknownst reasons, variability is the profession’s most unforgivable sin. But there is signal in variability which is lost in uniformity. And you can’t achieve uniformity without conformity, and forcing physicians to conform loses the valuable insights which come from individualism, the same quality which leads to variability.

Healthcare is a complex, recursive, wicked system. There is a place for Gauss but Gauss can’t be our sole method for analyzing healthcare. Antifragility is another framework for thinking about healthcare. Taleb’s prescription is a “barbell strategy” in which risk minimization and serendipity coexist. Healthcare should be designed, but not so perfectly or uniformly or optimally that it becomes too big to think. Imperfection must not just be tolerated but built into the system so that the system improves, as far as possible, on its own.

About the author:

Saurabh Jha is a radiologist and contributing editor to THCB. He can be reached on Twitter @RogueRad

Imagine if I told you that there was a pool of close to 600,000 individuals in New York City who were ripe for innovative health technology integration. You probably wouldn’t believe me and say that it sounded too good to be true. This said pool does in fact exist and can be found concentrated within the city’s public housing.

Imagine if I told you that there was a pool of close to 600,000 individuals in New York City who were ripe for innovative health technology integration. You probably wouldn’t believe me and say that it sounded too good to be true. This said pool does in fact exist and can be found concentrated within the city’s public housing.

The healthcare AI space is frothy. Billions in venture capital are flowing, nearly every writer on the healthcare beat has at least an article or two on the topic, and there isn’t a medical conference that doesn’t at least have a panel if not a dedicated day to discuss. The promise and potential is very real.

The healthcare AI space is frothy. Billions in venture capital are flowing, nearly every writer on the healthcare beat has at least an article or two on the topic, and there isn’t a medical conference that doesn’t at least have a panel if not a dedicated day to discuss. The promise and potential is very real.

How can parents help young children maintain a healthy attitude about dental care? First, children will follow your lead. If you are apprehensive about going to the dentist, your child will be, too. No one is born being afraid of the dentist; it is an acquired fear that can be quashed early on in a child’s life. Next, helping a child to brush at least twice a day and help with routine flossing will help maintain a healthy mouth. Children as young as age 2 or 3 can begin to use toothpaste when brushing, as long as they’re supervised to avoid ingestion of large amounts of toothpaste. Parents must work with children to teach good oral health habits. Tooth discoloration can also occur – sometimes caused from prolonged use of antibiotics or medications that contain a large amount of sugar. Parents should encourage children to brush after they take their medicine, particularly if the prescription will be long-term. Additionally, regular exams by a pediatric dentist are a critical part of maintaining your child’s oral health… but follow-up at home plays an equally important role.

How can parents help young children maintain a healthy attitude about dental care? First, children will follow your lead. If you are apprehensive about going to the dentist, your child will be, too. No one is born being afraid of the dentist; it is an acquired fear that can be quashed early on in a child’s life. Next, helping a child to brush at least twice a day and help with routine flossing will help maintain a healthy mouth. Children as young as age 2 or 3 can begin to use toothpaste when brushing, as long as they’re supervised to avoid ingestion of large amounts of toothpaste. Parents must work with children to teach good oral health habits. Tooth discoloration can also occur – sometimes caused from prolonged use of antibiotics or medications that contain a large amount of sugar. Parents should encourage children to brush after they take their medicine, particularly if the prescription will be long-term. Additionally, regular exams by a pediatric dentist are a critical part of maintaining your child’s oral health… but follow-up at home plays an equally important role.

Nazis and white supremacists.

Nazis and white supremacists.

The physician-patient relationship is a bedrock of the U.S. health system. Strong relationships are associated with higher ratings for physicians and better outcomes for patients but there’s a catch.

The physician-patient relationship is a bedrock of the U.S. health system. Strong relationships are associated with higher ratings for physicians and better outcomes for patients but there’s a catch.