By JONATHAN HALVORSON

Eventually, the share of the American economy absorbed by healthcare will stop rising. The question is when, and how much more collective damage will be inflicted in the process. As it turns out, there is a solution under our noses that is nearly ubiquitous in business, personal finance, and government programs worldwide. It can be used to bring manageable, relatively predictable transformation, rather than sudden wrenching change. It is a called a “budget.” It is well past time to embrace the discipline of budgets in healthcare financing.

Eventually, the share of the American economy absorbed by healthcare will stop rising. The question is when, and how much more collective damage will be inflicted in the process. As it turns out, there is a solution under our noses that is nearly ubiquitous in business, personal finance, and government programs worldwide. It can be used to bring manageable, relatively predictable transformation, rather than sudden wrenching change. It is a called a “budget.” It is well past time to embrace the discipline of budgets in healthcare financing.

The basic idea is clear: set a limit on how much money can be spent for healthcare. Almost every wealthy nation disciplines its spending with a budget for healthcare expenditures. The United States does not, still retaining for the most part an open-ended model in which rates for individual services are set, without overall limits on what is spent. The discipline brought by budgets allows other nations to spend roughly half what the United States does per person, despite the fact that life and health are valued in France, The United Kingdom, Israel, and Germany no less than in the United States.

Global healthcare budgets aren’t a policy of the left or the right. The use of budgets has become associated with the political right in America, despite the fact that nearly every socialized universal healthcare system in the world has one. The fact that this isn’t about left or right becomes clearer when considering that even in America both sides have advanced their own versions of capping healthcare expenditures by a budgeting mechanism.

The darling of conservatives for over 30 years has been the “block grant” for Medicaid. Starting with the Reagan administration in 1981, the basic idea has been to set a budget for a program according to a formula (say, last year’s cost plus an allowance for inflation). The block grant is given to a state, which then spends the money how it sees fit to accomplish program objectives. Since the state won’t see more dollars simply because providers are billing for more expensive services, or drug prices are increasing, the state has a strong incentive to find ways to manage those costs rather than simply pass most of them on to the federal government under the current system.

There are several problems with the basic block grant design, one of which is that it is not flexible with changes in economic conditions, such as a recession that brings a surge in the needy. To address this limitation, in their most recent proposals to cap the Medicaid program conservatives have adopted a modified approach that sets a spending limit per recipient rather than for the state overall. This is the “per capita” capped model which became the default in both the Ryan plan passed by the House of Representatives in April and the Senate version that came a few votes shy in July. For the per capita cap, the state’s budget effectively goes up in bad times and down in good times, so that the state can focus on how much is spent per Medicaid eligible person.

Seemingly unrelated to the Republican plans, the approaches preferred by progressive policy experts typically goes by the names “global budget” or “global cap.” New York, an azure blue state, has had a global cap for its Medicaid program since 2011. This cap on state Medicaid expenditures has brought great discipline to spending and saved New York taxpayers billions. The cap was part of a larger set of reforms initiated by New York’s Medicaid Redesign Team (MRT) in 2010 during a budget crisis brought on by the unsustainable growth of the Medicaid program. Over 270 of these reforms have been fully or partially implemented as of 2017. The other reforms enabled New York to live within the cap, and the cap in turn helped ensure the continuation of the reforms. The reforms cover benefit designs, rate changes, the expansion of managed care and new reimbursement methodologies, like value-based payment to reward outcomes over the volume of services. Every year new initiatives are proposed to stay within the budget.

And it has worked. Since 2011, New York has increased its Medicaid enrollment by over 1 million people while lowering the cost by about $1,000 per person. For a couple of those years, New York added large numbers of members to its rolls while at the same time lowering total program cost. This is unheard of in American healthcare, and the global cap was essential to making it possible. Lowering cost was temporary, but even now costs are growing much more slowly than prior to the global cap.

Maryland is another blue state that under Democratic leadership embraced global budgeting. Maryland, uniquely, had been living under some version of all-payer hospital rate setting in Medicare for over 40 years. Recently costs started to creep beyond the level approved by CMS, so Maryland moved to adopt true global budgeting to provide additional discipline. The new global budgets continue to set hospital payments for all payers, but they do so at the level of total hospital expenditures for the population, both inpatient and outpatient. Essentially, each hospital is given a pot of money based on its attributed patient population and other factors, and it is up to the hospital to spend it wisely (within limits). The new model produced nearly $116 million in savings in its first year of operation. Potentially avoidable readmissions dropped by 26% (nearly reaching the 30% five-year reduction target in the first year).

In Maryland the all-payer hospital growth rate is set at 3.6%. In New York, the services covered under the global cap are allowed to grow at the 10-year average Medical Consumer Price Index (CPI-M), which is about 3.6% currently. The House ACA-repeal bill capped Medicaid growth at the CPI-M from 2016 to 2019, with up to 1% additional growth allowed, which at current rates would be up to 3.7% annually. The Senate draft bill set the allowed growth rate at CPI-M for those not elderly or disabled from 2020 to 2025, after which it would switch to the general CPI for all urban consumers (CPI-U), which is historically over a percentage point lower.

While the Senate proposal is the stingiest, it’s clear that these caps are not far apart. Other initiatives, such as the all-payer statewide ACO in Vermont, also have growth caps in the range of 3.5%.The rhetoric presented in national debates unfortunately obscures the fact that these targets are closely related. But there’s a good reason they are similar: over the last 10 years GDP grew on average by less than 4% per year. In contrast, the 10-year average growth rate for Medicaid is 5.9% (partly due to Medicaid expansion under the ACA), and the overall growth rate for healthcare in the U.S. over that period was 4.9%. By staying below 4%, all of the proposals would reduce the share of the national economy devoted to Medicaid.

Of course, there are reasons that the rhetoric gets so heated. One of these reasons is that the budget is not created in a vacuum, and policies surrounding the cap can differ enormously. For example, Republicans didn’t just want to limit the rate of growth, they wanted to eliminate Medicaid’s expansion to new populations provided under the Affordable Care Act by slashing the funding available for those individuals, leaving an expected 10-15 million more people uninsured. And for Democrats, that is something worth fighting for.

In a battle to save coverage for millions, from a bill that they had no say in, it didn’t pay to be nuanced and single out parts of the legislation for compliment. But if that battle is over and voices of compromise can be heard, then global budgets provide the most promising path forward. Once on that path, and both parties agree that the solution is not to engage in dramatic cuts to eligibility but instead to reduce federal expenditures in the long term by capping growth, this would still save hundreds of billions of dollars over the next 10 years. There is much that Democrats and Republicans would still need to work out. For example, will states be allowed to pocket savings and not reinvest them into health promoting objectives? Will there be an escape hatch if states find themselves to manage some aspect of their costs (like pharmaceuticals), or even an option to revert to the older model? How much flexibility will states, insurers and providers have under such a system?

Failure is an option, of course. In adopting some version of global budgeting, we need to avoid what happened to the Sustained Growth Rate (SGR) formula in Medicare. The SGR set a growth rate in Medicare fee for service rates pegged to the actual total FFS expenditures in the prior year, but it was a formula that didn’t result in actual budgets. Once the actual reimbursement trend increased faster than the formula allowed, the framing around SGR almost immediately became that it was too harsh. Rather than rebalance rates, the standard refrain became that a “doc fix” was needed. Because the SGR wasn’t a true budget, the cuts it proposed were delayed year after year until eventually the SGR rule itself was rescinded. There are two lessons in this experience. First: guidelines don’t work; true budgets are needed. Second, and even more importantly: you can’t put a cap on just one of the three main pillars of American Health insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial) without the other two as well. If you’re a physician and your Medicare fees go up 1% every year while your fees for private insurance go up 5% every year, no matter how much more Medicare pays than what is typical in other wealthy nations, it is going to look like a “cheap” payer in the American context.

As some savvy readers of this article have no doubt been objecting for some time, that is also an insurmountable problem with the current Republican proposals to implement a budget-based cap on Medicaid expenditures alone. If Medicaid lives under a fixed budget but Medicare and commercial insurance do not, Medicaid will become even more of the poor-cousin payer. It will create more insolvent safety net hospitals because they are stuck in an environment where they have to compete on salaries, facilities and other matters with richer hospitals in a money-bloated system fueled by Medicare and especially by employer-based commercial insurance. More physicians will drop out of the program because they can be paid a multiple for their time elsewhere and their cost of doing business is in part set by the other forms of insurance.

And so at the same time as Medicaid switches to a capped, budget-based system, Medicare should as well. If Medicare does not follow, the cap in Medicaid will fail, sooner or later. Amazingly, New York Medicaid has been able to continue under a cap for 6 years, while Medicare and employer-based insurance grow with no such constraints. But partly that’s because New York started with one of the richest Medicaid programs in the nation and had room to cut excesses. There has also been an escape valve, in that parts of New York’s program have been outside the cap and allowed to grow at a higher rate, and CMS allowed some of New York’s savings to be recouped through a delivery system transformation program called DSRIP (over $6 billion dollars, in fact). But after 6 years of a global cap for most expenses, the Medicaid program in New York is feeling the strain. The collapse of the safety net provider network is inevitable if New York’s Medicaid program continues to stand alone.

As a bonus, once Medicaid and Medicare are locked together in a capped budget system, the environment will be conducive for employers and individuals who purchase commercial insurance to be open to a similar capped growth system to provide relief, creating an all-payer global budget approach that finally starts to look like the universal healthcare systems of Germany, The Netherlands, Israel, Switzerland and many other nations. (These are not single payer models. Those nations have robust, highly-regulated health insurance markets covering part or all of their health care expenditures.)

So why do budgets work? Normally when CMS or a private payer attempts to control some aspect of healthcare spending, it micromanages part of the delivery of care. Typically, this is effective for a short time until providers figure out a way around the barrier and alter the services delivered, or increase revenue by changing coding practices. But a budget puts an overall constraint on all spending, or a large enough portion of it to effectively prevent gaming.

Global budgets are consistent with many other objectives of healthcare reform. In fact, as shown in New York and Maryland, they can be a powerful stimulator to execute other reforms improving the quality of care, such as reducing avoidable ER visits and readmissions. By pushing responsibility for the financial management of care to providers, external parties (government and private payers) can start to get out of the business of micro-managing the practice of medicine and its administrative hassles, like utilization management.

A global budget can be formulated at many levels. Politically it can exist at the national, state, and regional level, with further distributions to individual managed care companies and/or providers, such as hospitals. To provide stability, a budget program should operate by a formula that can be projected out multiple years. The funds can be distributed to payers who are tasked to work with providers to stay within the caps. Or, the funds can be allocated centrally to specific provider organizations that are responsible for the spending of an attributed population, with insurance playing more the role of a pass-through. There are benefits and drawbacks to each approach. New York uses a mixed model of payer and provider responsibility, while Maryland and the rural Pennsylvania project focus on setting budgets for hospitals directly, while leaving office-based physicians in more traditional relationships with payers. Whatever the starting point, hospitals and other providers will need to take on risk for the cost of care and align their incentives with the efficient delivery of appropriate care. The move to budgets continues the transition to “value” that has dominated health care policy for over a decade.

Despite the political inertia that resists any major reform, the move to global budgets seems highly likely, eventually. It need not be a triumph of the pocketbook over the heart. Affordability is not a dry goal for lifeless bean-counters. The high cost of healthcare brings bankruptcy, despair, suicide, and diverse dreams deferred or abandoned for the uninsured and poorly insured, and even for some who thought they were well-insured. A long term healthcare budget growth rate that is 0.4 percent less than the long term growth in GDP will mean that every year healthcare costs get a little easier to bear. After some years, the belt-tightening period would be over and growth would increase again to match the overall economy. Rather than one-time cuts that hurt those with few resources most, Republicans should focus on doing what they campaigned on: keeping everyone covered at a lower cost…modified with the boring but essential caveat that “lower cost” is relative to the growing economy, not a big one-time drop in nominal dollars. Democrats know that it is not in the national interest for healthcare to keep absorbing more and more of every dollar earned, and that it undermines Democratic objectives such as achieving universal healthcare. They should embrace the discipline of budgets to accomplish this. We don’t need to keep taking the path of maximal pain.

Jonathan Halvorson is a consultant on healthcare policy and strategy for Sachs Policy Group. He is formerly the Director of Operations and Systems for the New York State Office of Health Insurance Programs, which administers New York’s Medicaid program. The views expressed here are his own.

A bipartisan group of health policy experts has issued a call to action and well-thought-out consensus plan for insurance market stabilization and incremental reform.

A bipartisan group of health policy experts has issued a call to action and well-thought-out consensus plan for insurance market stabilization and incremental reform.

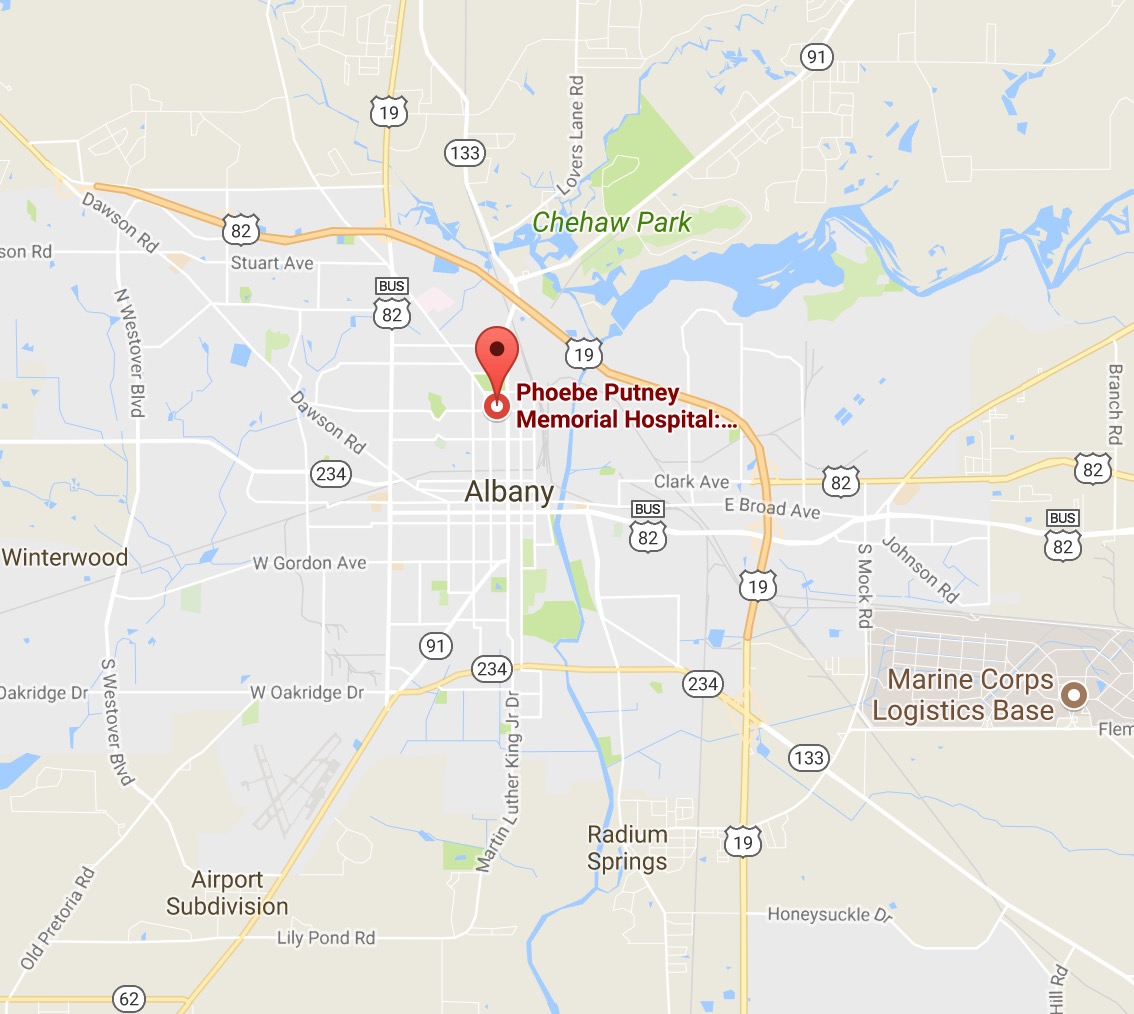

As hospital consolidations sweep the nation, the monopolies being created are having a profound impact on life in small town America. Lee County, in Southern Georgia, is a little place with big dreams; they are resolutely determined to build a 60-bed community hospital and provide local residents with real choices. For years, two competing hospitals served the population of 200,000 spread over six counties: Phoebe-Putney and Palmyra Park. Phoebe-Putney Memorial Hospital put an end to that by securing a 939-bed hospital monopoly and an ample market share.

As hospital consolidations sweep the nation, the monopolies being created are having a profound impact on life in small town America. Lee County, in Southern Georgia, is a little place with big dreams; they are resolutely determined to build a 60-bed community hospital and provide local residents with real choices. For years, two competing hospitals served the population of 200,000 spread over six counties: Phoebe-Putney and Palmyra Park. Phoebe-Putney Memorial Hospital put an end to that by securing a 939-bed hospital monopoly and an ample market share.

In biology, it is clear that access to more genes leads to greater overall health. This is true because it allows for a greater likelihood that a genetic defect can be compensated by a gene from a different pool. This is the reason that inbreeding leads to more genetic diseases. This same phenomenon exists in social science. Complex social networks are healthier than more narrow (constrained) ones. Dr. Amar Dhand of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Department of Neurology has, for example, shown that people are more likely to get to the emergency room in time to receive a clot busting therapy for stroke if they are part of a more complex, rather than constrained, social network.

In biology, it is clear that access to more genes leads to greater overall health. This is true because it allows for a greater likelihood that a genetic defect can be compensated by a gene from a different pool. This is the reason that inbreeding leads to more genetic diseases. This same phenomenon exists in social science. Complex social networks are healthier than more narrow (constrained) ones. Dr. Amar Dhand of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Department of Neurology has, for example, shown that people are more likely to get to the emergency room in time to receive a clot busting therapy for stroke if they are part of a more complex, rather than constrained, social network.

A study published recently in JAMA Internal Medicine showed financial rewards and connected pill bottles don’t work. One explanation suggests that “other patient concerns about potential adverse effects of these medications, such as impotence or fatigue, were not targeted by this engagement strategy.”

A study published recently in JAMA Internal Medicine showed financial rewards and connected pill bottles don’t work. One explanation suggests that “other patient concerns about potential adverse effects of these medications, such as impotence or fatigue, were not targeted by this engagement strategy.”

Eventually, the share of the American economy absorbed by healthcare will stop rising. The question is when, and how much more collective damage will be inflicted in the process. As it turns out, there is a solution under our noses that is nearly ubiquitous in business, personal finance, and government programs worldwide. It can be used to bring manageable, relatively predictable transformation, rather than sudden wrenching change. It is a called a “budget.” It is well past time to embrace the discipline of budgets in healthcare financing.

Eventually, the share of the American economy absorbed by healthcare will stop rising. The question is when, and how much more collective damage will be inflicted in the process. As it turns out, there is a solution under our noses that is nearly ubiquitous in business, personal finance, and government programs worldwide. It can be used to bring manageable, relatively predictable transformation, rather than sudden wrenching change. It is a called a “budget.” It is well past time to embrace the discipline of budgets in healthcare financing.