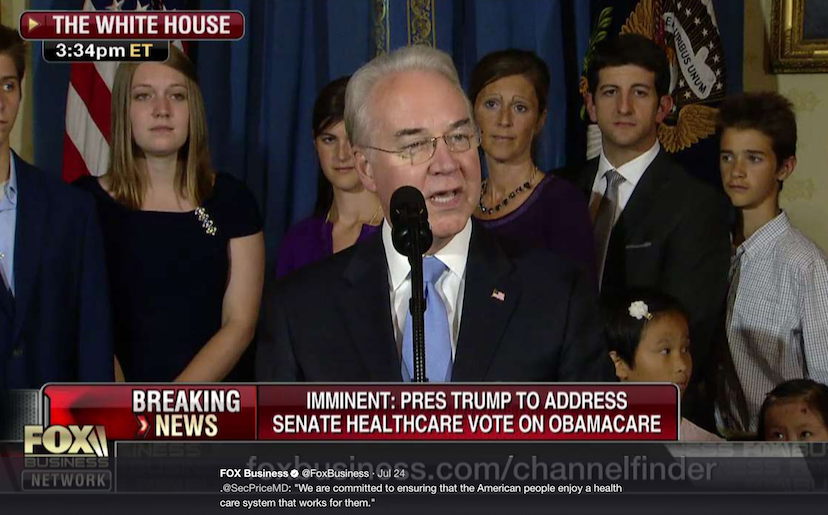

As is customary for every administration in recent history, the Trump administration chose to impale itself on the national spear known as health care in America. The consequences so far are precisely as I expected, but one intriguing phenomenon is surprisingly beginning to emerge. People are starting to talk about single-payer. People who are not avowed socialists, people who benefit handsomely from the health care status quo seem to feel a need to address this four hundred pound gorilla, sitting patiently in a corner of our health care situation room. Why?

The all too public spectacle of a Republican party at war with itself over repealing and replacing Obamacare is teaching us one certain thing. There are no good solutions to health care within the acceptable realm of incremental, compromise driven, modern American solutions to everything, solutions that have been crippling the country and its people since the mid-seventies, which is when America lost its mojo. To fix health care, we have to go back to times when America was truly great, times when the wealthy Roosevelts of New York lived in the White House, times when graduating from Harvard or Yale were not cookie cutter prerequisites to becoming President, times when the President of the United States conducted meetings while sitting on the toilet with the door open and nobody cared. Rings a bell?

Single-payer health care is one such bold solution. Listening to the back and forth banter on social media, one may be tempted to disagree. We don’t have enough money for single-payer. Both Vermont and California tried and quit because of astronomic costs. Hundreds of thousands of people working for insurance companies will become unemployed. Hospitals will close. Entire towns will be wiped out. Doctors will become lazy inefficient government employees and you’ll have to wait months before seeing a doctor. And of course, there will be formal and informal death panels. Did I miss anything? I’m pretty sure I did, so let’s enumerate.

Single-payer is going to bankrupt the nation

We have $3 Trillion in our health care pot right now. We have 325 million Americans, men women and children of all ages. First grade arithmetic says we have almost $10,000 per year to spend on each American, the vast majority of whom is either young or healthy or both. For comparison, Medicare spends on average around $12,000 per year for the oldest and sickest population. Last year a platinum plan for a 21 year old cost less than $5,000 per year and this includes the built in waste of private health insurance. So please, tell me again how we can’t afford to pay for everybody’s health care needs at a Medicare actuarial level, which is slightly less than commercial platinum.

And no, we need not increase taxes either. You keep paying what you’re paying. Your employer keeps paying what it is paying. The government keeps paying what it’s paying. But instead of dispersing all that cash to all sorts of corporate entities standing in line with their golden little soup bowls ready to catch the last drop, we put it all together in one big beautiful barrel, and pay for care directly to those who provide care – one pool, one budget, and one accounting system for all. This is a national endeavor. It is irrelevant that Vermont failed and California bungled the whole thing. Do you think California and Vermont could afford to provide for their own armies, air force and navies? I didn’t think so.

Single-payer will cause millions to lose their jobs

Hundreds of thousands of people work for commercial insurers. Claims need to be processed, money needs to be collected and paid out, books need to be kept, customers and service providers need to be supported, computers have to be maintained, audits need to be performed, contracts need t be managed, lots and lots of labor and lots and lots of decently paying jobs. Do you have any idea how Medicare administration works? Or are you under the impression that Medicare runs itself with no human labor? Have you ever heard of Noridian or Cahaba? No? Then I respectfully suggest that you should refrain from opining about the horrors of single-payer.

Medicare is run by private administrative contractors called MACs, each assigned to specific geographical regions and specific portions of Medicare services. In addition to the MACs there are slews of functional contractors that specialize in one or more types of supporting services to the MACs. These are private entities no different from Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Hewlett-Packard, Booz Allen Hamilton, GE and many more. They employ thousands of people and if Medicare becomes our single-payer, there will be more MACs, more functional contractors, and hundreds of thousands more private employees.

That said, it stands to reason that consolidation from many payers to one, will introduce some efficiencies and the total number of available jobs will be reduced, so here is a solution to this potential problem. Currently all insurers including Medicare and Medicaid are offshoring claim processing and in the case of private insurers other functions, including clinical, as well. Change the regulations and bring those jobs back home where they belong in the first place, and offer them to those who will lose their commercial insurance jobs. This administration is especially well positioned to effect such changes to CMS regulations.

Single-payer will take away our freedom

What if Sam’s Club only carried General Mills cereal and Costco only carried Kellogg’s? What if you had a Costco membership but stopped by another store to pick up some Cheerios and were charged ten times as much as Sam’s Cub sells it for? No it’s not exactly the same, but you get the idea. Would you consider this to be freedom of choice? Or would you rather have one big huge market where all brands sell their products directly to you competing against each other? The latter is how single-payer could work. Freedom to shop for an insurance plan is freedom to shop for your preferred rationing scheme and ultimately your own flavor of death panel.

Traditional Medicare allows you to choose your doctor and your hospital and it pays for all medically necessary services. No commercial plan can say the same unless it’s one of those platinum things nobody can afford. Traditional Medicare can do that because it sets the prices for all health care providers, instead of negotiating with a few preferred vendors. Medicare can take these liberties because it’s big enough and because it’s a Federal program. But Medicare doesn’t pay for everything. That’s why most seniors purchase supplemental plans if they can afford them, and if they are poor enough, Medicaid kicks in as the secondary payer. Being the safety net for the fixed price single-payer should be the sole function of a new and federally administered Medicaid.

Single-payer will destroy our health care

I think American medicine is the best in the whole world. Not because it’s expensive and not due to the corrupt ways in which it’s being financed, but in spite of these things. Finding a better way to pay our medical bills has nothing to do with the quality of American medicine. The concern here is that once Medicare becomes the only game in town, it will unilaterally cut its fee schedules and all hospitals will go bankrupt, all doctors will be driven into homelessness, no new drugs will be developed and we’re all going to die. On the other hand, the Federal government is the sole purchaser of aircraft carriers, stealth bombers, and weaponry of all types. How cheap are those items? How powerless and decrepit is that industry?

Precisely because of the lessons learned from the mighty military industrial complex, single-payer reform will have to change three things in the structure of our current so-called health care system. First, all hospital consolidation and acquisition of physician practices will need to be rolled back. Second, petty regulations, vindictive carrots and sticks strategies and crude attempts at social engineering by clueless bureaucrats, will have to be dismantled brick by brick. Third, physicians will need to form a union of independent small contractors to negotiate fees and terms alongside the already powerful hospital associations. I have been a longtime proponent of a physicians’ union, even in our current system, to serve as check and balance to corporate greed and government arrogance. A single-payer system cannot and will not succeed without unionized independent physicians.

Single-payer is not the American way

We have been conditioned by large corporations to think that what they do to us is the nature of free-markets, and thus the only way to achieve prosperity for all. I would submit (for the millionth time) that what Apple is doing to the world has nothing to do with Adam Smith’s free markets. The actors in classic free markets must be approximately equal. When sellers are so big that they need artificially intelligent tools to even notice the existence of buyers, there is no free market. When the price of products sold exceeds the lifetime incomes of most buyers, there is no free market. When no one can muster enough moral turpitude to publicly say that if you’re poor, your babies should die, there is no free market. There is no free market and there can be no free market in health care.

There can however be competition. Perhaps not in sparsely populated areas, and perhaps not for highly complex procedures, but there can be competition for most health care services in most places. The uniform single-payer price should be set so that innovative hospitals and entrepreneurial physicians can thrive by charging less and those holding themselves in higher than usual esteem, or those who choose to provide luxury, are free to charge more. If all sellers are small enough, and if the standard single-payer price is fairly negotiated, we will have a real market, because people will shop to save money (in a rewards system like credit cards have) and some will shop for status and vanity.

Will there be a role for private insurance? There could be, but private insurance should not be allowed to cover any services covered by the single-payer because that would take us back to where we are today. Let private insurance cover stuff nobody needs, but wealthy people like to flaunt, like fresh baked brioche for breakfast after having a baby, or executive physicals in palatial settings, and let those things become frightfully expensive, as these types of things usually are in a free market.

Single-payer will create a new set of losers. Health care executives making tens of millions of dollars every year for no particular reason will be losers. Perhaps they can find new careers at Boeing or Lockheed Martin seeing how their expertise is easily transferable. Health insurance stocks will tank and improperly managed pension funds will also lose bigly. People running for elections will see a major cash cow go dry after the initial struggle is over and done with. There will be powerful losers and it won’t be easy.

But Obamacare has its losers too. Hard working, taxpaying middle class citizens were the designated losers of Obamacare. Some by commission and most by omission, because Obamacare made no attempt to solve the health care problems facing the vast majority of workers with employer sponsored health insurance. That bomb keeps ticking away at a steady pace. The newly empowered Republican Party has nothing to offer either, and I can’t blame them. There is nothing more we can do here. We tried everything else, and now it’s time to do the right thing. It’s the American way.

This Spring,

This Spring,

Health care providers love to vaunt the unique and subtle needs of patients. How many ads have you heard from cancer centers or health clinics touting their flexibility and showing grateful, tear-flecked patients?

Health care providers love to vaunt the unique and subtle needs of patients. How many ads have you heard from cancer centers or health clinics touting their flexibility and showing grateful, tear-flecked patients?