On the golf course, my son Jason has an uncanny ability to hit any tree within earshot of his intended target line. It’s fait accompli in his book. And his reaction is always the same: “seriously!”

On the golf course, my son Jason has an uncanny ability to hit any tree within earshot of his intended target line. It’s fait accompli in his book. And his reaction is always the same: “seriously!”

The same is his plight with health insurance. Though a self-employed healthy single male with a successful career and no need for government assistance in buying coverage, he just got this letter from his insurer:

“The last seven years within the health insurance market have led all of us to decisions we have never before considered. It has remained a very challenging environment as the debate over the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) continues today.

At TRH Health Insurance Company, we have arrived at another critical decision point, which, unfortunately, will affect you. This letter (and the enclosed notification letter as required by the ACA) is our notice that we will not be offering plans in the non-subsidized marketplace in 2018. Your current plan remains effective through December 31, 2017.”

It’s the third time in five years he’s been dropped. Though paying his premiums dutifully and shrinking his coverage to reduce his monthly cost, his premium has increased more than 10% every year. And he’s healthy.

As the GOP Senate leadership weighs its options in moving toward a Repeal of the Affordable Care Act and its replacement, their greatest political risk is the potential that up to 22 million will lose their insurance coverage per the Congressional Budget Office’ most recent score. They have bet their political calculus on stories like Jason’s, one of 18 million in the individual insurance market whose premiums have skyrocketed. More than 8 million of these get a subsidy to buy their policy because their incomes fall below 400% of the federal poverty level. Those subsidies are likely to go away. For the rest, like Jason, it’s a crap shoot. Individual insurance plans that feature less coverage, narrow networks, high premiums, high out of pocket costs and the high likelihood the underwriter will cancel the policy the next year is standard fare. Or, they just choose to go without.

The July 4 recess gave Senate Majority Leader McConnell a week to tweak the BCRA to get the requisite 50 votes needed to pass a bill. Repeal of the individual mandate, major cuts to Medicaid programs and tax breaks for insurers, drug and device manufacturers and higher income households are still in. The proposed sweeteners fall into two buckets:

- Bucket One: Changes to funding for special programs: To accommodate a few Senators, $45 billion to fund the opioid addiction program is being added and delays in cuts to Planned Parenthood are on the table.

- Bucket Two: to accommodate insurers so they don’t raise premiums too high or exit the individual market altogether: the addition of a six-month waiting period on coverage for those who let their coverage lapse, allowing consumers to use funds from their Health Savings Accounts to pay their premiums, and a provision to allow states to determine their own medical loss ratio requirements for individual and group insurance plans.Stabilizing the individual market so people like Jason can get a plan that’s affordable and predictable is complicated. But these are the realities:

The regulatory constraints imposed by the Affordable Care Act on insurers are flawed. Medical loss ratio requirements of 80% for the individual market and 85% for the group market are too high, especially when coupled with elimination of caps on life-time limits, coverage of pre-existing conditions, inclusion of all 10 essential health benefits in every plan and age-rated risk bands set at 3:1 instead of 5:1 as plans had operated previously. Insurers are advancing some of the most innovative ways to address chronic disease management in innovative arrangements with providers, so lawmakers should revisit how they define “medical loss” (which is an unfortunate term to describe medical care). And the penalty for non-coverage is too low incent young invincibles to buy coverage. That’s why the marketplaces attracted more sick and older than the government’s actuaries expected. Coupled with higher administrative costs associated with individual health plans, it’s a non-starter for insurers. Tackling the individual market for insurers is only part of the issue facing insurers: flaws in the ACA’s oversight of insurance extend beyond the individual market.

- Insurers have no obligation to provide coverage to any segment in the population if it’s not profitable to their businesses. Insurance companies, whether investor-owned or not -for-profit plans like the 36 Blues operate in the interests of their owners. Even provider-sponsored health and co-ops have the same obligation: to spend premiums cautiously and cut unnecessary costs. All take risks in underwriting the plans they sell, adjust their premiums annually to cover medical inflation and utilization costs, modify coverage to reduce costs and purge their enrollments when higher-than-anticipated costs or utilization shows up in their claims data. The insurance business is complicated and risky. Like hospitals and post-acute providers, health plan operating losses are common, and margins are thin. But unlike hospitals, they can choose to cover who they wish and suspend services if they can’t make their numbers work. Hospitals don’t have that luxury.

- Americans want coverage but most don’t trust insurers. The majority of Americans associate coverage with access to physicians and hospitals they prefer and protection against personal financial ruin if they are in the 5% who experience an accident or contract a disease requiring expensive care. Most think insurance is too expensive and don’t understand why premium hikes are high across the board. Most think insurers will drop anyone who’s too risky or costly to the plan and most don’t see any difference between a plan sponsored by a medical group or health system and one owned by investors. Insurers know this: they struggle to make their cases to legislators, providing ample data to support their premium increase requests, denial policies and results of the population health programs they sponsor. But trust in health insurance companies is negative though the majority think coverage is necessary. Go figure. For lawmakers, satisfying the public’s growing aversion to escalating health costs and sensitivity to insurance premiums is not easy.

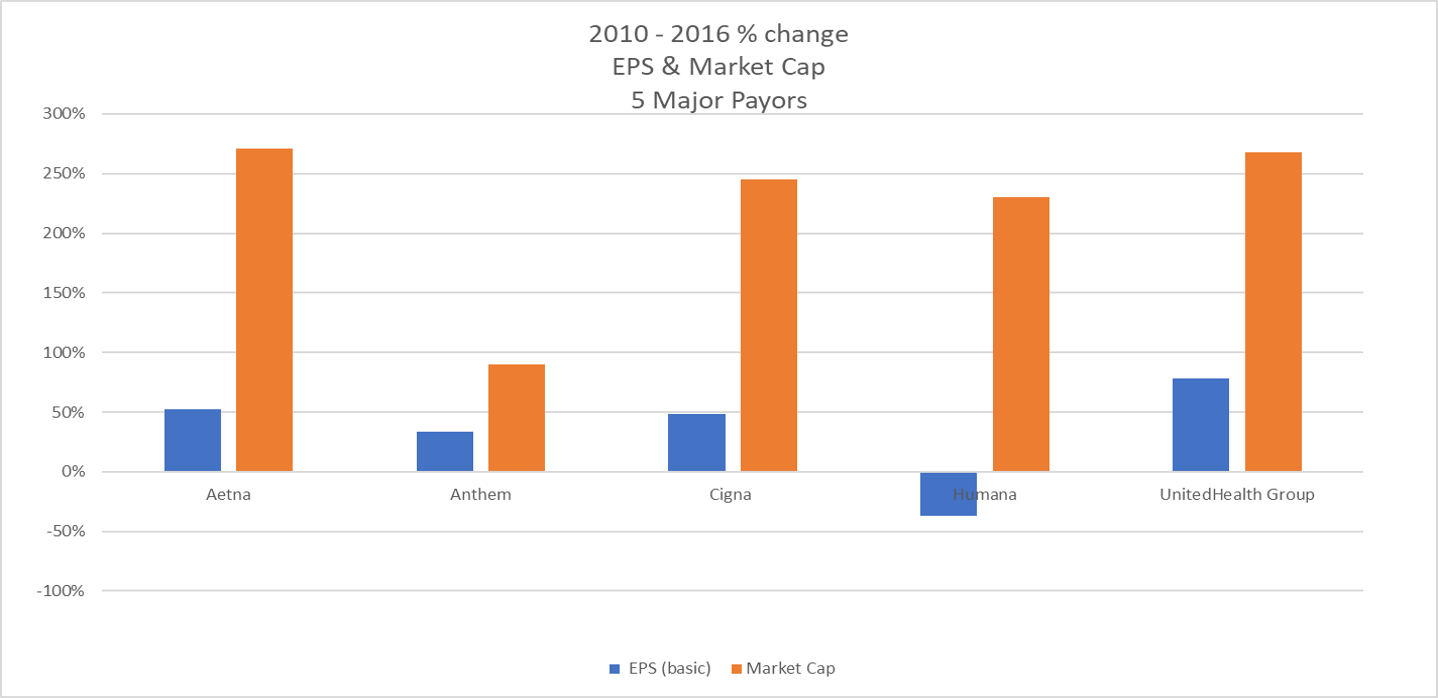

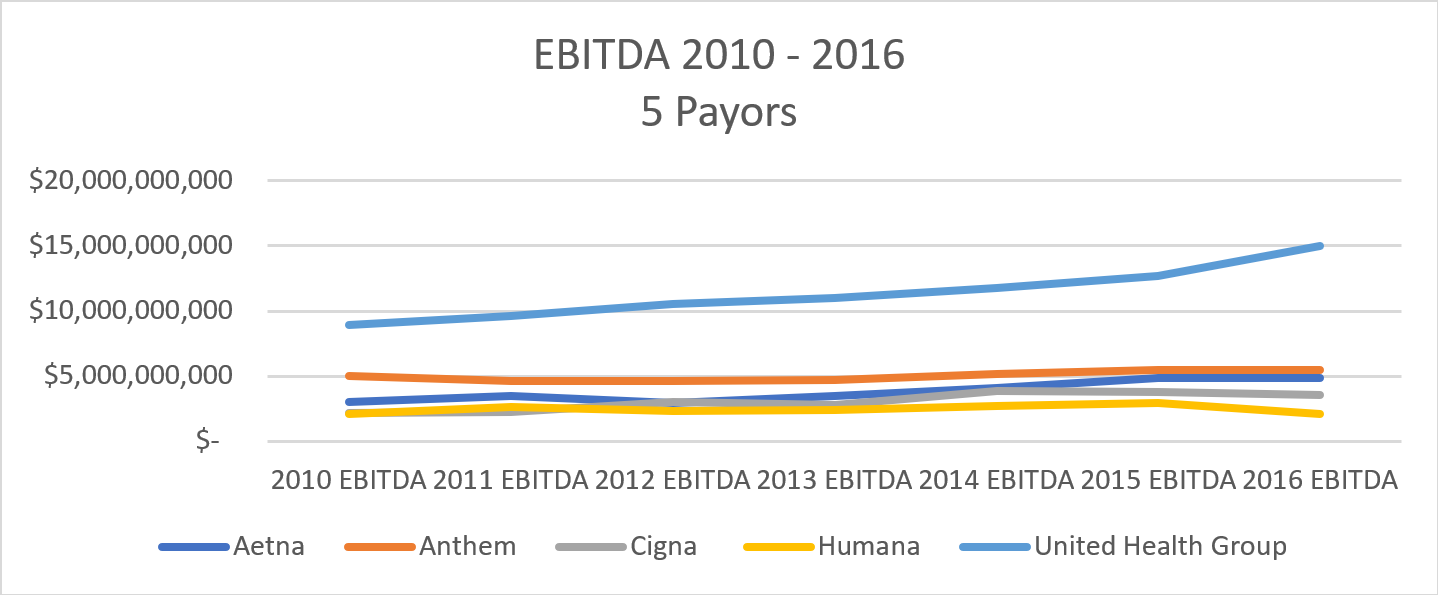

- Large Insurers have done well since passage of the ACA despite its flaws, while others have been hurt. Like other industries, scale is an advantage. While it’s difficult to access data about the financial performance of non-publicly traded health plans, financial data from the Big Five (Aetna, Anthem, Cigna, Humana and United who control 44% of the insurance market and have a market cap approaching $300 billion) show the advantage of scale. Since passage of the ACA, the market capitalization for each has more than doubled. EBITDA (earnings before taxes, interest, depreciation and amortization—a measure of operating profit) have steadily improved with recently stalled at Cigna and Humana and basic EPS (earnings per share) have improved annually for 4 of the 5. (See The Keckley Group analysis of financial reports from the Big Five for 2010-2016 below). All insurers have tightened their operations and lowered their administrative costs. Many have purged their plans of the riskiest populations precipitating decisions like withdrawal from the individual market and exchange marketplaces. Almost all have invested in sophisticated information systems and coding to optimize their rebates from the reinsurance pool (CMS announced Friday that 445 of 709 would get something back, and larger plans fared well). And most have diversified into non-insurance ventures to mitigate their insurance risks long-term. Example: in the June 19, 2017 Bloomberg Businessweek, United Healthcare Optum’s 3-page ad touts its capabilities in Data and Analytics. Pharmacy Care Services. Population Health Management. Health Care Delivery. Health Care Operations. The data show that plans with the largest enrollments have fared considerably better than others, in spite of the ACA’s flaws and current uncertainty about what’s ahead.

The bottom line is this: insurance as we know it seems destined for radical change. The largest plans seem advantaged by the uncertainty around the Repeal and Replace efforts in DC and they’ll be stronger and bigger. Smaller plans will not survive. Some will focus exclusively on Medicare and Medicaid managed care. Some will carve out certain populations of high risk enrollees. Some will transform themselves into diversified health services companies. And, for the foreseeable future, regardless of what becomes of the BCRA, they will raise their premiums above medical inflation because we’re getting older and the costs of our drugs, technologies and hospital stays are increasing.

This scenario puts lawmakers in a precarious position: by conceding to insurer demands of fewer restrictions on the policies they sell, they expose citizens to coverage that’s cheaper but less comprehensive. And eliminating the mandate to buy coverage means large numbers of healthy young adults might forego coverage, take their chances and pay the penalty. It’s an irony: Americans see the need for coverage but it leaves a bad taste in our mouths.

Jason and I talked about his situation. He’s compared notes with his buddies: they’re confused about their own insurance. Matt runs a successful business: he says he knows how to predict and plan for every expense in his business…except healthcare. Bret works for a big company: he’s counting on it to continue his family coverage and figure it out. And Jason’s looking for a new plan but skeptical about his prospects. He doesn’t want or need a government subsidy and he doesn’t understand how the partisan rancor in Washington fixes anything. He’s too young to think about health issues everyday but he’s forced to think about it every year. Especially now that he’s another statistic in the displaced health insurance marketplace.

For Jason, having to find coverage and paying a higher premium for less coverage is like hitting trees on the golf course: it’s fait accompli. Seriously!

Paul

Dr. Jha writes on these pages in typically stirring fashion about his views on the recent health care kerfuffle and rightly so fingers what the real focus of our efforts should be: Cost. He ends by slaying both sides because of their refusal to confront the hospital chargemonster – the fee schedule hospitals make that remarkably only really applies to the uninsured.

Dr. Jha writes on these pages in typically stirring fashion about his views on the recent health care kerfuffle and rightly so fingers what the real focus of our efforts should be: Cost. He ends by slaying both sides because of their refusal to confront the hospital chargemonster – the fee schedule hospitals make that remarkably only really applies to the uninsured.

When the eminent physician Dr Cliff Cleveland wrote his memoir about his years in medical practice, he entitled his book, “Sacred Space.” Yes, it’s a bit sentimental, but he pays rightful homage to the idea that that relationship between patients and their doctors and nurses is something exceedingly precious. Medical professionals appropriately go out of their way to keep that space neutral, private and nonjudgmental, because patients are often at their most vulnerable.

When the eminent physician Dr Cliff Cleveland wrote his memoir about his years in medical practice, he entitled his book, “Sacred Space.” Yes, it’s a bit sentimental, but he pays rightful homage to the idea that that relationship between patients and their doctors and nurses is something exceedingly precious. Medical professionals appropriately go out of their way to keep that space neutral, private and nonjudgmental, because patients are often at their most vulnerable.

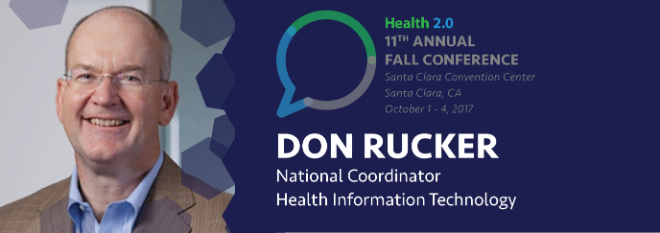

We are pleased to announce that Don Rucker, National Coordinator for Health Information Technology at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will be a featured speaker and a panelist at our upcoming Health 2.0 11th Annual Fall Conference,

We are pleased to announce that Don Rucker, National Coordinator for Health Information Technology at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will be a featured speaker and a panelist at our upcoming Health 2.0 11th Annual Fall Conference,