By KIP SULLIVAN

In my first post in this three-part series, I documented three problems with Pioneer ACOs: High churn rates among patients and doctors; assignment to ACOs of healthy patients; and assignment of so few ACO patients to each ACO doctor that ACO “attributees” constitute just 5 percent of each doctor’s panel. I noted that these problems could explain why Medicare ACOs have been so ineffective.

These problems are the direct result of CMS’s strange method of assigning patients to ACOs. Patients do not decide to enroll in ACOs. CMS assigns patients to ACOs based on a two-step process: (1) CMS first determines whether a doctor has a contract with an ACO; (2) CMS then determines which patients “belong” to that doctor, and assigns all patients “belonging” to that doctor to that doctor’s ACO. This method is invisible to patients; they don’t know they have been assigned to an ACO unless an ACO doctor tells them, which happens rarely, and when it does patients have no idea what the doctor is talking about. [1]

This raises an obvious question: If CMS’s method of assigning patients to ACOs is a significant reason why ACOs are not succeeding, why do it? There is no easy way to explain CMS’s answer to this question because it isn’t rational. The best way to explain why CMS adopted the two-step attribution method is to explain the method’s history.

I will do that in this essay. We will see that Congress, on the basis of folklore, decided that doctors in the traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare program were ordering too many services and needed to be herded into “physician groups” that would resemble HMOs (see my comment here on the obsession with overuse). But Congress also decided they didn’t want to force Medicare beneficiaries to enroll with the quasi-HMOs. That was a critical decision because it required that Congress figure out some method other than enrollment to determine which patients “belonged” to which physician groups. Congress, in its Infinite Wisdom, decided they would let someone else figure that out. They assigned that task to CMS.

The assignment was impossible. CMS should have told Congress they were nuts but, understandably, CMS eschewed that option. So CMS did the best they could. Based on some arbitrary assumptions, CMS devised the two-step assignment method that is now causing so much trouble for ACOs.

The first mistake: Demonizing fee-for-service

The label “accountable care organization” was invented by Elliott Fisher and members of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission at MedPAC’s November 9, 2006 meeting. [2] At that meeting Fisher presented to MedPAC a version of the two-step process for assigning Medicare beneficiaries that CMS was already using for the Physician Group Practice (PGP) demonstration (which began in 2005) and that CMS would go on to use for its first two ACO programs – the Pioneer ACO program and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) (both inaugurated in 2012). That fact, and Fisher’s aggressive promotion of ACOs after that meeting, earned Fisher the title of “father of the ACO.”

But the ACO concept was being discussed by CMS by the early 1990s (at that time CMS was known as the Health Care Financing Administration), and the two-step method of assigning patients to groups of doctors was being discussed within CMS by the early 2000s. The impetus for these discussions was a series of laws enacted by Congress in1989, 2000, 2005, and 2010, all aimed at reducing inflation in the cost of Medicare’s traditional FFS program.

In the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1989, Congress authorized a “volume performance standard” (VPS) for Part B, the first version of what would soon become the Sustainable Growth Rate formula (which would in turn be replaced by MACRA in 2015). The VPS was a limit on total Part B spending. Because Congress had some doubts about how well the VPS would work, and perhaps more importantly, because Congress had bought the conventional wisdom that FFS causes overuse and overuse was causing health care inflation, Congress included a provision within OBRA authorizing CMS/HCFA to develop an alternative to Part B’s FFS method. This alternative was supposed to employ managed care tactics, including shifting insurance risk to doctors.

This was the first mistake Congress would make on its way to endorsing ACOs and ultimately MACRA. By demonizing FFS and lionizing managed care, Congress got it totally backwards. Congress should have investigated how to make both the insurance industry and the privatized portion of Medicare (what we now call Medicare Advantage) look more like traditional Medicare, not the other way around. By the early 1990s Congress had been warned numerous times that there was little evidence for the claims being made on behalf of HMOs and the HMO wannabees that were rapidly taking over the insurance industry, and much evidence indicating that the portion of Medicare run by HMOs (today’s Medicare Advantage) was costing much more per insured beneficiary than the traditional FFS program. [3]

But Congress, under the spell of the managed care movement, didn’t grasp that it had it backwards. So rather than instruct CMS to look for ways to induce private-sector insurers to act more like traditional FFS Medicare, Congress endorsed the opposite policy. Provisions in OBRA instructed CMS to start looking for ways to make the traditional Medicare program look more like the managed care insurance companies that were taking over the private sector.

The sound of one hand clapping

Predictably enough, the VPS system authorized by OBRA didn’t work and Congress replaced it with the doomed Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula in 1997. The SGR soon proved it wasn’t going to work either.

The problem with both the VPS and SGR (aside from the fact they were designed to address overuse, a problem that was minor compared to underuse and excessive prices and administrative costs) was that they both applied expenditure growth limits to the entire pool of 700,000 American doctors who treated Medicare patients. That pool was too large; there was no way individual doctors could perceive that it was in their self-interest to reduce their own contribution to the alleged overuse problem by cutting back services to their own patients.

By the late 1990s, Congress and the managed care movement were even more obsessed with overuse and, given the failure of the VPS and SGR mechanisms, even more determined to find a way to break the ocean of Medicare doctors into smaller pools to which mini-SGRs and managed-care tactics could be applied. The thinking was that if doctors were no longer in a pool of 700,000 doctors but were instead in much smaller pools (say 200 to1,000 doctors), doctors would find it in their financial interest to stop ordering all those unnecessary services and, if they didn’t, they could be micromanaged by a third party.

The failure of the VPS and then the SGR led Congress to enact two laws that contained provisions that accelerated the search for the Holy Grail – quasi-HMOs that could serve as the holding pens for pools of doctors much smaller than the national pool. The first of these laws, the Medicare, Medicaid, and State Child Health Insurance Program Benefits Improvement and Protection Act (BIPA) of 2000, authorized CMS/HCFA (hereafter just CMS) to create the Physician Group Practice demo, and the other, the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, instructed the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) to dream up some other small-pool ideas. It was the 2005 instructions to MedPAC that caused MedPAC to hold that November 9, 2006 meeting with Elliot Fisher at which the “ACO” label was invented and endorsed. MedPAC’s endorsement in turn contributed significantly to the groupthink that induced Congress to include provisions in the Affordable Care Act authorizing CMS to start the Pioneer and MSSP ACO pilots.

The BIPA law of 2000 was the second in which Congress asked CMS to solve the Zen riddle they refused to solve – how to determine “belongingness” of patients to doctors without making patients enroll with a doctor or clinic. But this time CMS would have to do more than produce a study on how the impossible question might be answered. This time they would have to choose a method and use it in an actual demonstration – the PGP demo. There could be no more delay. CMS had to solve the Zen riddle presented to them by Congress – it had to devise a way to assign patients to groups of doctors so that those doctors could be punished if “their” patients got too many services even if many of those patients, um, weren’t “theirs.”

Solving the unsolvable

After Congress passed OBRA, CMS contracted with scholars at Brandeis to make recommendations on how to expose groups of doctors to financial incentives to reduce medical services. The Brandeis scholars delivered their first paper on “group specific volume performance standards” to CMS in 1991, and subsequent installments in 1992 and 1995 (see their 1995 paper here and a 2003 version of it here ).

These papers proposed the basic elements of what would later be called the ACO. They proposed “shared savings” programs under which groups of doctors allegedly large enough to bear some insurance risk would somehow cut medical costs and share the savings with CMS. CMS would measure savings (or, perish the thought, increased costs) by calculating total spending on all the patients seen by a “physician group” in a baseline year, and then compare that with total spending on the patients seen by that group in a subsequent (“performance”) year. The Brandeis papers regurgitated the folklore peddled by the dominant managed care movement, to wit:

- FFS was responsible for “runaway” growth in Part B spending (whether growth was even more “runaway” in the private sector didn’t matter);

- “managed care” was the solution;

- under the lash of exposure to insurance risk, doctor groups would adopt managed care tactics;

- those tactics would generate savings and improve quality, not the other way around;

- CMS would find a way to measure physician cost and quality accurately; and

- the savings would be shared between Medicare and the doctors.

The Brandeis papers offered no evidence for these claims. [4]

Although the Brandeis scholars acknowledged in their reports that Congress didn’t want Medicare recipients to be forced to enroll with physician groups, they dodged the question of how, short of forced enrollment, CMS would know which recipients belonged to which doctors. [5] It was not until the early 2000s, when CMS began planning the PGP demo, that CMS “solved” that problem. Sometime shortly before the 2005 inauguration of the PGP demo, CMS adopted the peculiar two-step method of assigning patients that they would use in the PGP, Pioneer, and MSSP programs.

When CMS began designing the PGP demo, they contracted with RTI International, not the Brandeis scholars. In a paper published in a 2007 edition of Medicare and Medicaid Research Review, RTI’s John Kautter and colleagues laid out the design of the PGP demo they had recommended and that, by then, CMS had adopted. Kautter et al. stated their recommendations “build on” the Brandeis papers, then went beyond the Brandeis studies and proposed an algorithm by which CMS could assign Medicare beneficiaries to the ten groups participating in the PGP demo.

Kautter et al. recommended that CMS first determine to which PGPs doctors belonged, and then assign patients to those doctors based on the plurality-of-primary-care-visits method. Under this method, patients would be assigned to the primary doctor they saw most often. Thus, if I see two primary care doctors during a baseline year (say 2017) a total of five times, and three of those visits were to Dr. Inside ACO and two were to Dr. Outside, I will be assigned to Dr. Inside during the performance year (say 2018). Even though I’m free to see Dr. Outside and other doctors in 2018, and even though I may never again visit Dr. Inside after 2017, Dr. Inside is still “accountable” for me in 2018.

Kautter et al. did not comment on the irrationality of the riddle posed to CMS by Congress. They merely declared, “Because the PGP demonstration is a Medicare FFS innovation, there is no enrollment process whereby beneficiaries accept or reject involvement. Therefore, we developed a methodology to assign beneficiaries to participating PGPs based on utilization of Medicare-covered services.” Having thus delicately skirted the issue of congressional sanity (don’t you just love the unctuous phrase “FFS innovation”?), they went on to say they used two criteria to determine the best assignment method:

We evaluated the alternative assignment methodologies on two criteria: Provider responsibility and sample size. First, providers must believe that the numbers and types of services they provide mean that they have primary responsibility for the health care of beneficiaries assigned to them. Otherwise, PGPs may have difficulty responding effectively to the demonstration incentives…. Second, sample size is critically important for the statistical reliability of performance measurement. If the number of beneficiaries assigned to a participating PGP is too low, then cost and quality performance measurement may be unstable.

Note the phrase “providers must believe.” How did Kautter et al. determine what doctors “must believe” about how turbulent the pool of patients assigned to them should be? Answer: They interviewed a few doctors. What did the doctors tell them? Kautter et al. didn’t say. How did Kautter et al. determine what constitutes accurate “performance measurement” and how big the pool of patients must be to achieve that? They didn’t say. They simply concluded that when they balanced the two criteria in their own minds – “responsibility” and sample size – they came up with the plurality-of-visits method.

Kautter et al. simulated their plurality-of-visits method and discovered it would cause great churn among patients. “PGPs generally retained approximately two-thirds of their assigned beneficiaries from one year to the next,” they reported. How did Kautter et al. justify such a high churn rate? Other than to say they interviewed some doctors, they didn’t. They also had no comment on the possibility that the two-step process would assign few patients to doctors and that those patients might be healthier than average.

Sometime shortly before CMS implemented the PGP demo in 2005, CMS adopted Kautter et al.’s two-step assignment method for that demo. In November 2006, the ineffable phrase “accountable care organization” was concocted by Fisher and MedPAC. And sometime between the enactment of the Affordable Care Act in March 2010 and the 2012 start date of the Pioneer and MSSP ACO programs (probably 2011), CMS decided to use the same two-step method they had adopted for the PGP demo for those ACO programs.

We have seen the consequences. PGPs/ACOs can’t cut costs and, at best, make modest improvements on a tiny handful of quality measures, an improvement which may have been accompanied by a decline in the quality of unmeasured care.

No exit

If you followed my discussion of how Kautter et al. struck a balance (at least in their own minds) between their two criteria – “belongingness” and adequate sample size – then you already know that the problems created by CMS’s two-step assignment method are not fixable.

Consider CMS’s only option to reduce patient churn. If CMS abandons the plurality-of-visits rule in favor of, for example, an 80-percent-of-visits rule, that would greatly increase the odds that the patients assigned to a doctor really do “belong” to that doctor and will continue to see that doctor in the performance year. But that would also assign even healthier patients to ACOs, and it would greatly reduce the number of patients that could be assigned to ACOs. The reduction in the number of patients assigned to ACOs would in turn make CMS’s measurements of cost and quality even cruder, and it would push the percent of ACO patients in a doctor’s panel even lower than the 5 percent level I discussed in my previous post.

ACO proponents have only two options: Explicitly prohibit patients from visiting doctors outside their ACO, which would be tantamount to admitting ACOs really were HMOs in drag all along; or redefine ACOs so that they are no longer responsible for entire “populations” but instead focus on the chronically ill. I will discuss these options, the impact these options would have on MACRA, and the final Pioneer ACO evaluation in my next post.

[1] Evidence on the near-total lack of awareness among patients of their assignment to an ACO appears in the final evaluation of the Pioneer ACO program, released last December. The author of that evaluation, L&M Policy Research, held focus groups with Medicare recipients who had been assigned to a Pioneer ACO. “[W]e learned that beneficiaries were generally unaware of the ACO organization and the term ‘ACO,’” L&M reported. “In the few cases where the beneficiaries reported hearing the term ACO, they were not able to describe what an ACO is and its relationship to them as recipients of health care services. Since beneficiaries were not even aware of the term ‘ACO,’ they also were unaware that their care was being provided or coordinated by an ACO.” (p. 51)

Patient ignorance of their status as an ACO member may have been aggravated by physician ignorance. According to L&M, “In several respects, physicians were not particularly knowledgeable about the ACO. When asked if they knew which of their patients were aligned with the Medicare ACO, just over a third of Pioneer physicians reported knowing which beneficiaries were aligned and a similar proportion reported not knowing their aligned beneficiaries at all. When asked about the elements of their compensation, almost half of physicians participating in the Pioneer model reported not knowing whether they were eligible to receive shared savings from the ACO if the ACO achieved shared savings.” (p. 43)

[2] As Kelly Deverson and Robert Berenson put it, “Together, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission … and [Elliot] Fisher provided the impetus for the current concept and interest in ACOs.” (p. 2)

[3] It should have been obvious to Congress why traditional FFS Medicare was beating the pants off the insurance industry. First, the traditional Medicare program paid doctors and hospitals substantially less than private-sector insurers did. Second, the traditional program devoted a much smaller percent of its expenditures to overhead (2 percent since the early 1990s) compared with the 20-percent overhead of the insurance industry. (For evidence that the insurance industry’s overhead is 20 percent, see this graphic published by America’s Health Insurance Plans. For evidence that traditional Medicare’s overhead is 2 percent, see citations to reports by the Medicare trustees, the Congressional Budget Office and others in my paper on this subject in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law.) The insurance industry has never figured out how to overcome those two advantages – lower payment to providers and lower overhead – and it never will.

Moreover, as of the early 1990s the traditional Medicare FFS program did not micromanage Part B doctors as the insurance industry did and as MACRA is forcing CMS to do today. That in turn meant traditional Medicare was not driving up physician overhead costs, and was not burning doctors out, anywhere near as much as the insurance industry did and does now.

[4] Here is just one example of numerous evidence-free paeans to HMOs and managed care strewn throughout the Brandeis papers produced under contract with CMS, then HCFA: “The efficiencies … should be achieved through effectively managed care…. Presence of utilization review and quality assurance programs and other features associated with managed care may also be prerequisite.” (“Models for Medicare payment system reform based on group-specific volume performance standards (GVPS),” unnumbered page, Appendix B )

[5] The authors of the Brandeis papers might object to my statement that they “dodged” the issue of how to assign patients to physician groups. They could argue, correctly, that they did mention the issue and decided they didn’t need to assign patients to each doctor. I won’t try to explain here the strange logic they used to justify that position. Suffice it to say their primary argument, presented without a shred of evidence, was that risk adjustment could accurately detect changes in the average health status of an ever-changing pool of patients.

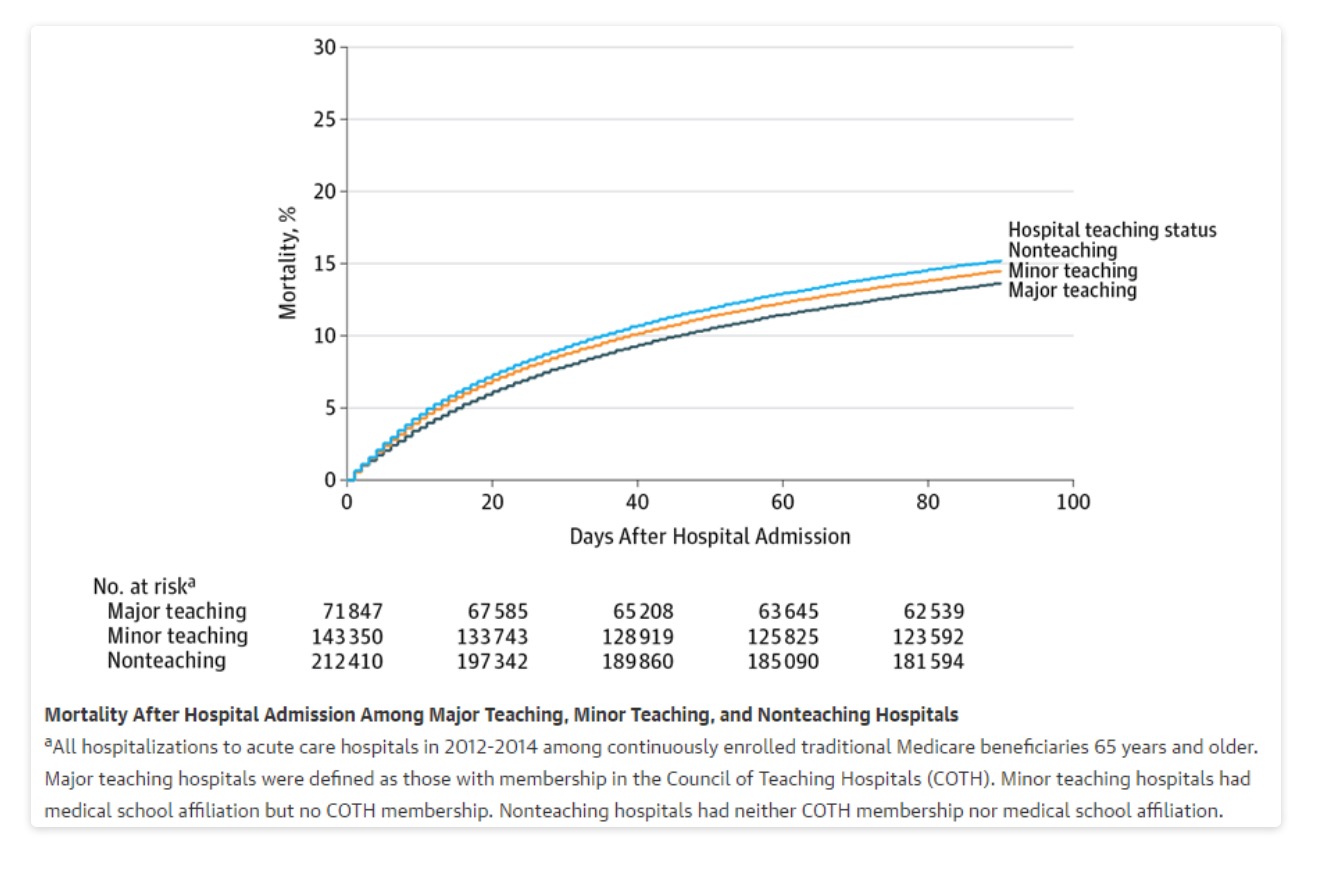

How much does it matter which hospital you go to? Of course, it matters a lot – hospitals vary enormously on quality of care, and choosing the right hospital can mean the difference between life and death. The problem is that it’s hard for most people to know how to choose. Useful data on patient outcomes remain hard to find, and even though Medicare provides data on patient mortality for select conditions on their Hospital Compare website, those mortality rates are calculated and reported in ways that make nearly every hospital look average.

How much does it matter which hospital you go to? Of course, it matters a lot – hospitals vary enormously on quality of care, and choosing the right hospital can mean the difference between life and death. The problem is that it’s hard for most people to know how to choose. Useful data on patient outcomes remain hard to find, and even though Medicare provides data on patient mortality for select conditions on their Hospital Compare website, those mortality rates are calculated and reported in ways that make nearly every hospital look average.

In late March of this year, JAMAInternal Medicine published a study finding that the “the overall rate of [malpractice] claims paid on behalf of physicians decreased by 55.7% from 1992 to 2014.” The finding wasn’t new. In 2013, the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies published a study co-authored by one of us (Hyman) which found that “the per-physician rate of paid med mal claims has been dropping for 20 years and in 2012 was less than half the 1992 level.” In fact, peer-reviewed journals in law and medicine have published lots of studies with similar results. It is (or should be) common knowledge that claims of an ongoing liability crisis are phony.

In late March of this year, JAMAInternal Medicine published a study finding that the “the overall rate of [malpractice] claims paid on behalf of physicians decreased by 55.7% from 1992 to 2014.” The finding wasn’t new. In 2013, the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies published a study co-authored by one of us (Hyman) which found that “the per-physician rate of paid med mal claims has been dropping for 20 years and in 2012 was less than half the 1992 level.” In fact, peer-reviewed journals in law and medicine have published lots of studies with similar results. It is (or should be) common knowledge that claims of an ongoing liability crisis are phony.