By ANISH KOKA, MD

A GOP congress may never again get a chance to kill so many people. Could rival the Iraq war in its total.

— David Cutler (@Cutler_econ) June 22, 2017

11. Overall, for every ~300 to 800 adults who get coverage, rigorous studies suggest we save one life per year.

— Atul Gawande (@Atul_Gawande) June 21, 2017

I remember 7 South at the Children’s hospital very well. I remember the distinctive smell, the large rooms, the friendly nurses, and Shantel. For a brief period of time, Shantel and her little boy – a too skinny child named James – were there every time I was there with my little girl. 7 South was the GI floor – Shantel and I were there because our children had the same dastardly liver disease that, for the time being, was winning. And that was it. We had nothing else in common.

She grew up in North Philadelphia, not far from where I was finishing a residency program in Internal Medicine. She had three other children, was a single mother, and in the year that I spent shuttling to the hospital I never saw the father of her child. Shantel did not work, and relied almost exclusively on the welfare programs to make life work.

I was a medical resident, our family had a combined income north of $150,000/ year, and our health insurance was through my employer. My wife and I worked, which meant that we had the flexibility for one of us to stop working, and still maintain our benefits.

Shantel, I am sure, did not have such luxuries. Regardless, it is one of the beautiful things about America that James had the same opportunity at life as my child – their hospital room was no different than mine, their doctors were my doctors, the medications prescribed were the same, and access to a liver transplant list was determined by medical need, not the size of one’s bank account. Walking through the hospital doors in America is like going through a magic portal – contrast this to the resource limited developing world, where families frequently need to bring the medications their family needs to the hospital to be administered.

Much of the debate now about Medicaid cuts is ostensibly about James and Shantel. The debate as it is carried out, (by serious people!), is more Hulk Hogan vs the Machoman Randy Savage than it is Ali/Frazier. The analysts on television and social media would seem more interesting in marshaling outrage than actually discussing how best to care for those who have not. At the moment, the left finds itself under siege from the right, hungry to roll back the federal expansion of the last 8 years, and in their defense have rolled out the really big gun – science. The experts from the most hallowed sites in the land now claim that any attempt to reform medicaid amounts to a death sentence for Americans.

It is important to note that none of the experts speaking out against Medicaid reform identify themselves as partisans. They cloak themselves in evidence, and speak not about theories or possibilities, but the certainty of what they know based on science. In this case, in order to argue for an expanded role for government in delivering healthcare, the left finds its most powerful argument to center around the lives saved by health insurance and the lives lost without a mechanism to deliver health insurance.

Does health insurance save lives?

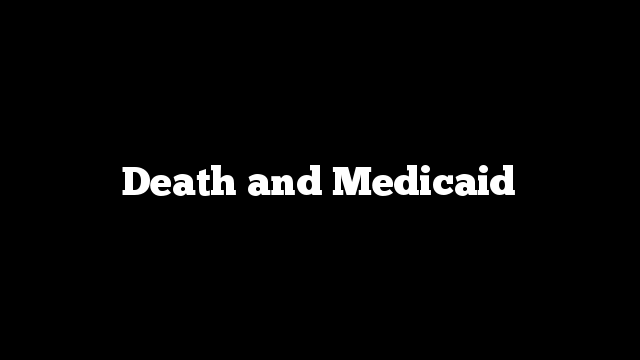

A timely editorial summarizing the evidence related to health insurance recently appeared in the widely acknowledged bible of medicine – the New England Journal of Medicine – to ‘inform’ the debate on public policy. The authors are distinguished, well- recognized names from the Harvard community that go on to discuss a large body of research that they have largely helpfully, and impressively generated.

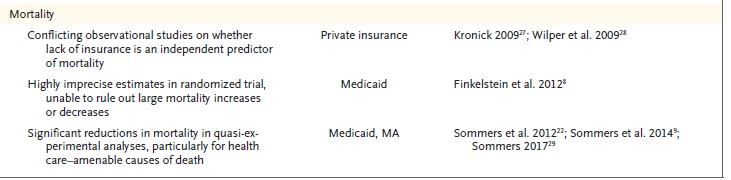

The problem with connecting insurance and mortality is that it is incredibly hard to prove causation. The vast majority of studies on this topic and all topics are observational studies because that comprises the vast amount of data that currently exists. The problem, of course, is that the uninsured patient population is a very distinct population from insured patients. Any analyses require accounting for confounding variables using self reported behavior, health status, and socioeconomic variables. This still leaves omitted variables that are either unknown or unmeasurable, and perhaps hardest of all remains susceptible to reverse causality. It is entirely possible, that underlying health status drives the choice to have health insurance. Thus, it is entirely possibly that the claim that good health results from insurance may be like saying wind results from windmills. This is an incredibly vexing problem for those shaping to move public policy with evidence which has the approximate value of adulterated bullshit. A level up from parsing large observational trials is what’s called quasi-experimental studies, where health insurance status is unrelated to the choices patients make. Medicare came into being in 1965 and bestowed insurance on Americans once they were 65. If health insurance results in lives saved, one would expect mortality rates in the Medicare covered over 65 population to go down relative to the under 65 population. It doesn’t. As seen in this visually compelling figure from Finkelstein & Mcknight in 2005, the institution of Medicare in 1965 had no impact on mortality.

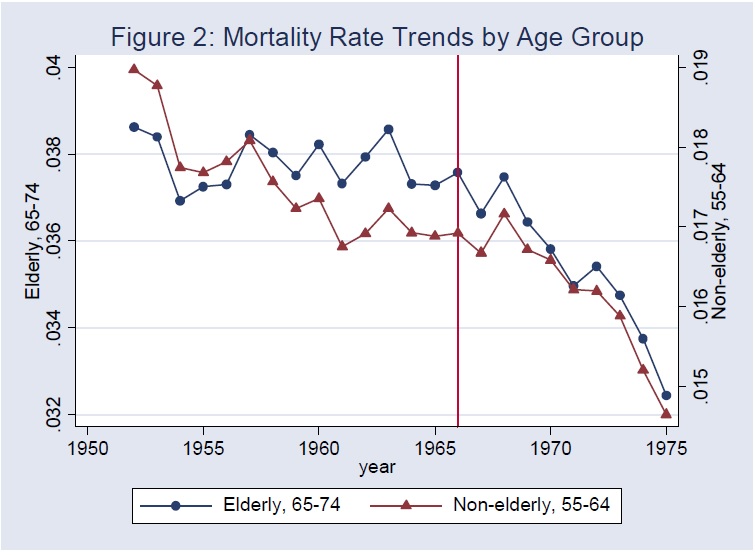

If only we had data in this space where uninsured patients were randomly assigned via a lottery to receive insurance. Remarkably, this happened in Oregon in 2008 when Medicaid expansion was decided based on a random lottery. Oregonians who were able bodied, and uninsured and whose household income was less than 100% of the Federal Poverty level had to enroll in a lottery if they wanted health insurance. A study of 12,000 patients over 2 years demonstrated no difference in multiple surrogate measures of health such as blood pressure, cholesterol or diabetes control. Predictably, the expert analysis of the data had much to do with your prior belief in the role government should play in health insurance. Those that believe health care is a right to be insured by the government focused on the limitations of the study, while conservative analysts accepted the natural conclusion that health insurance had little to do with positive health outcomes. Undeterred by this data, and seeking to go beyond the limitations of the small size of the Oregon study, Sommers and Co. (author of the NEJM review) proceeded to do a quasi-experimental study of three Medicaid expansion states. Sommers et al., use a difference in difference analysis – a statistical tool used to mimic a randomized control trial and account for comparing populations that don’t have the same starting point. I can’t pretend to understand the various methods used in the analysis, but the results of this larger quasi-experimental study suggests medicaid expansion in the 3 states resulted in lower mortality. As a way to provide plausibility for the reduction in mortality, a helpful graph is provided that looks at one of the conditions ‘amenable’ to medical care – HIV mortality.

HIV mortality does seem to decrease markedly in expansion states, ostensibly due to the expanded availability of antiretrovirals – but interestingly, the mortality reduction in this case seems to be decreasing significantly prior to medicaid expansion. So the only hard conclusion to come to about Medicaid and mortality is that nothing is certain. This doesn’t keep Dr. Sommers from taking to the pages of USA Today to use his ‘iron clad’ evidence to balance the ‘political rhetoric’ that insurance may not save lives. And so it is that the randomized control trial evidence is dismissed, and minimized by the proponents of Medicaid. The summary of evidence provided by Dr. Sommers in the NEJM refers to the only randomized control trial data as ‘highly imprecise data unable to rule out a mortality increase or decrease’. It is ironic that the a high priests of evidence takes a position with this level of evidence – I can’t imagine Sommers and company would be willing to approve a drug that was unable to show a mortality difference in a 12,000 patient randomized control trial, and had conflicted observational/quasi-experimental data. The casualty in this speculative endeavor where overreach reigns is is the credibility of the science of health care policy and its practitioners.

The funny thing is that I frequently take a stand with experts against what I find to be a selective interpretation of data. I find it dangerous to ignore experts in their field solely because their expertise creates implicit bias. I would be willing, and have been in the past, to give the coterie of experts in public health their due if it wasn’t for the fact that their expertise is applying statistics to big data, and not actually taking care of patients. The onus is not on me to find the fundamental flaw in their work – it is for them to convince clinicians whose charge it is to actually manage health conditions that Medicaid as it is currently designed would improve hard patient outcomes. From my vantage point, I have a difficult time understanding how Medicaid in its current form improves hard outcomes with chronic care management as has been suggested. Mr. Garfinkel has refused to stop smoking for the four years I have known him, takes his aspirin when he feels like it, and does not like how his blood pressure medication makes him feel. His only visits to me relate to acute illnesses, and he sees me because my wait time for urgent appointment is same day rather than the 3 weeks his primary care physician gives him. Mr. Ramos is currently in the hospital with a bleed in his brain from uncontrolled hypertension. I counted ten no-shows over the course of the last year. It is true I could have done more, it is possible I could have tried to remotely manage Mr. Ramos’s blood pressure. With a Medicaid plan that pays between $30 – $40, even non-profit medical centers that charge $1000 for a bag of saline shy away from Medicaid patients – how could physician practices do better?

Thus, it comes as no surprise to me that mortality is a heavy lift that is probably too heavy for insurance to bear, and I need a lot more than quasi-experimental data to change my mind. There is some value to health insurance – patients are happier, and have protection from medical bankruptcies- but is that worth the $550 billion dollars we spent on Medicaid in 2015?

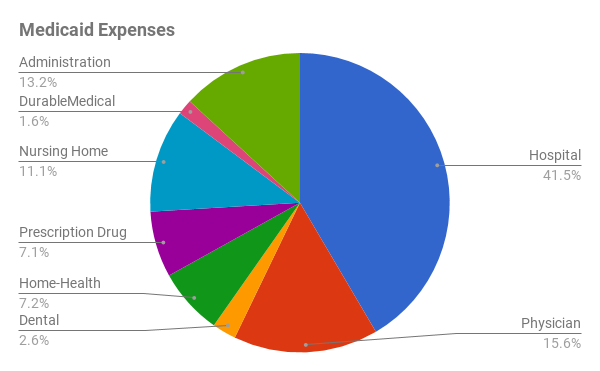

Medicaid can and should be better, but at the moment I see no plans to reform Medicaid that would help the physicians charged with taking care of this population. If public health policy experts are actually concerned about chronic care that may work to avoid some of the 40% of Medicaid dollars spent in hospitals, and give doctors a shot at improving outcomes that matter, it may help to resource physicians on the front lines better. The Healthy Indiana Plan, set up by the current CMS administrator, Seema Verma, used tobacco tax dollars to raise medicaid rates to equal medicare rates. While this is a promising start that at least tries to solve the challenge Medicaid patients face when trying to access elective care, it could go much further. Allow Medicaid patients to use federally funded HSA’s to pay physicians a monthly subscription of as little as $50-$100/month, which would make actual major strides towards the ambulatory care of medicaid patients.

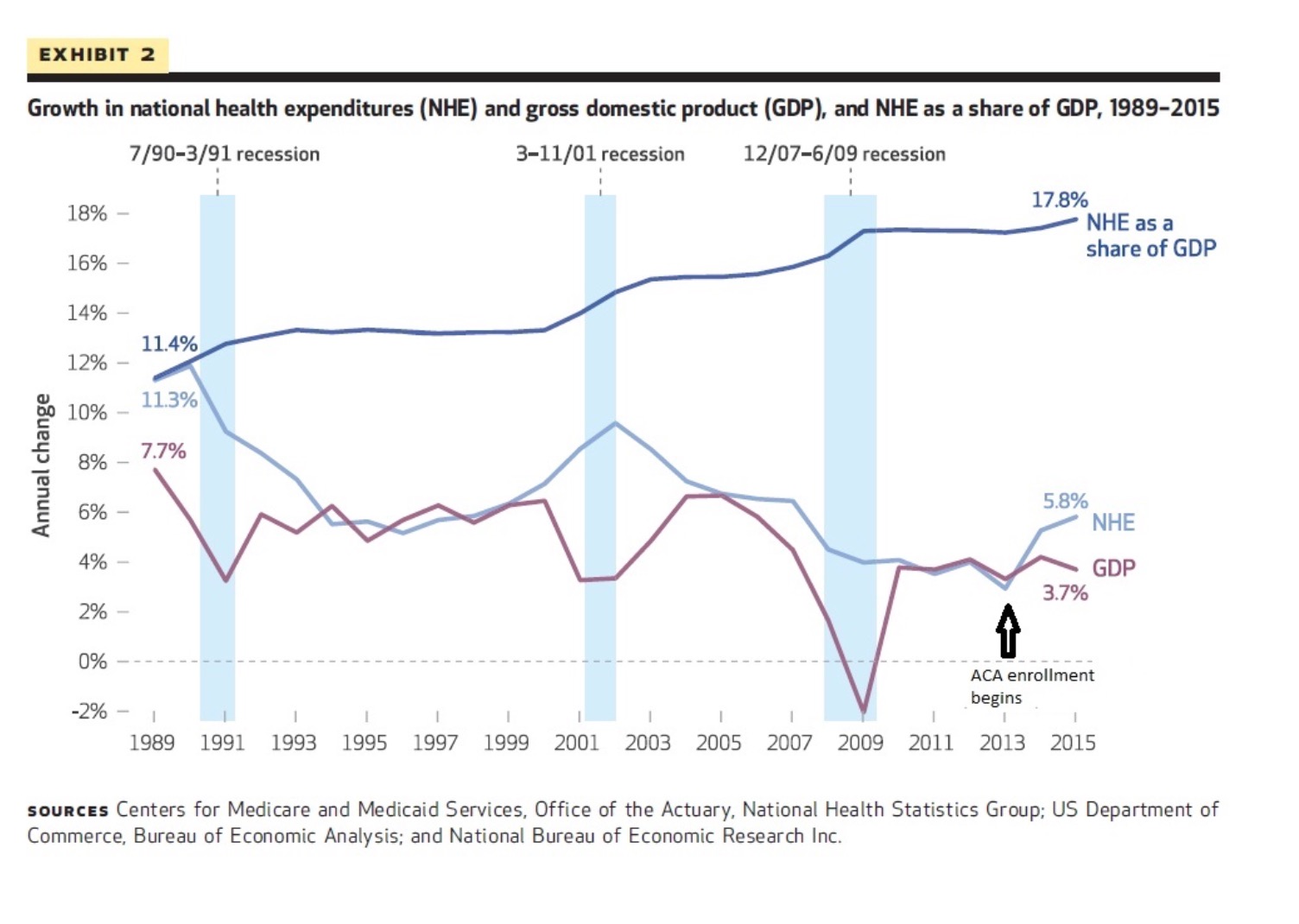

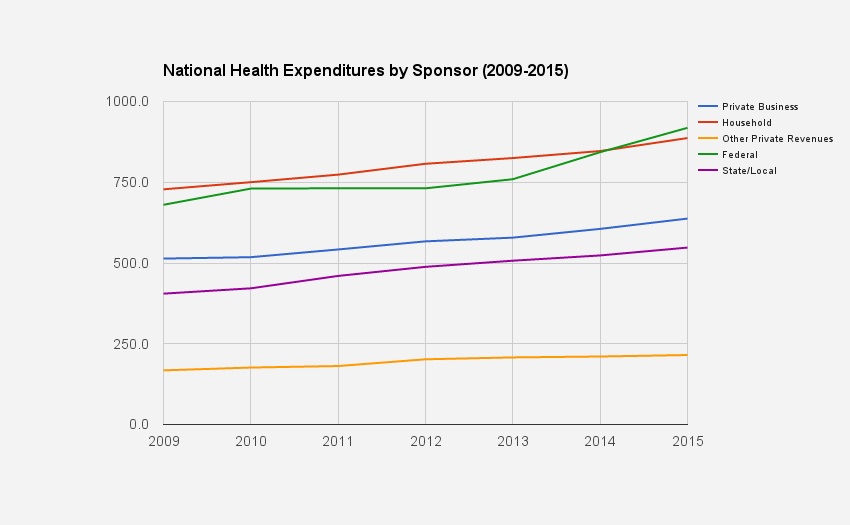

The truth is that I’m an optimist when it comes to Medicaid. At the moment, the federal government matches 51% for every dollar spent by the states on Medicaid patients with no cap. Driven primarily by Medicaid expansion, national health expenditures that had been flat relative to GDP prior to 2014, started to rise again. This is an unsustainable path.

Medicaid can and should be better, but at the moment I see no plans to reform Medicaid that would help the physicians charged with taking care of this population. If public health policy experts are actually concerned about chronic care that may work to avoid some of the 40% of Medicaid dollars spent in hospitals, and give doctors a shot at improving outcomes that matter, it may help to resource physicians on the front lines better. The Healthy Indiana Plan, set up by the current CMS administrator, Seema Verma, used tobacco tax dollars to raise medicaid rates to equal medicare rates. While this is a promising start that at least tries to solve the challenge Medicaid patients face when trying to access elective care, it could go much further. Allow Medicaid patients to use federally funded HSA’s to pay physicians a monthly subscription of as little as $50-$100/month, which would make actual major strides towards the ambulatory care of medicaid patients.

The truth is that I’m an optimist when it comes to Medicaid. At the moment, the federal government matches 51% for every dollar spent by the states on Medicaid patients with no cap. Driven primarily by Medicaid expansion, national health expenditures that had been flat relative to GDP prior to 2014, started to rise again. This is an unsustainable path.