There are 80,000 new cases of primary brain tumors diagnosed every year in the United States. About 26,000 of these cases are of the malignant variety – and John McCain unfortunately joined their ranks last week. In cancer, fate is defined by cell type, and the adage is of particular relevance here.

There are 80,000 new cases of primary brain tumors diagnosed every year in the United States. About 26,000 of these cases are of the malignant variety – and John McCain unfortunately joined their ranks last week. In cancer, fate is defined by cell type, and the adage is of particular relevance here.

Cancer is akin to a mutiny arising within the body, formed of regular every day cells that have forgotten the purpose they were born with. In the case of brain tumors, the mutinous cell frequently happens to not be the brain cell, but rather the lowly astrocyte that normally forms a matrix of support for brain cells. Tumors made up of astrocytes are called astrocytomas. Classification schemes for brain tumors in the era of molecular subtypes has grown enormously complex, but a helpful framework is provided by the appearance of these tumors under a microscope. Grade 1 tumors are indolent, with little invasive capacity, while Grade 4 tumors are highly invasive, marked under the microscope as dense, sheets of cells that can even be seen to grow their own blood supply. Senator McCain has a grade 4 astrocytoma, otherwise known a a glioblastoma (GBM) – the worst kind. Social media from all sides of the political spectrum lit up with well wishes – with most casting the disease as something to be defeated.

John McCain is an American hero & one of the bravest fighters I’ve ever known. Cancer doesn’t know what it’s up against. Give it hell, John.

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) July 20, 2017

Others within the medical community took a different take.

GBM sucks & will defeat McCain. “Get Well Soon” is misguided to point of being insensitive.This is where ‘thoughts and prayers’ makes sense.

— Mehreen (@GrrlMD) July 20, 2017

Mehreen is right. GBM is a deadly disease, the 5-year survival rate for patients with GBMs is <3%. The majority of GBM patients live less than a year. Yet, the medical community of neurosurgeons and oncologists that treat these tumors go to battle with these tumors. Why?

I asked a very busy neurosurgeon this same question. I asked him what he told patients. He told me that he never mentions the word cure. There is no cure. The goal is to manage the disease and buy more time.

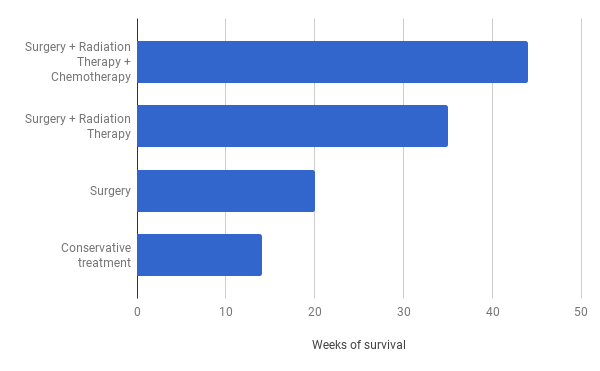

Median survival for GBM is measured in weeks, not years. Do nothing, and expect 14 weeks; combining surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy may give you 45 weeks.

What we describe is median survival, of course, and as Stephen J Gould eloquently put in his diatribe against statistics in cancer – the median is hardly the message. The oncologist you want is the one who doesn’t tell you about median survival when breaking the news to you of your cancer – she implicitly understands each GBM has a different path. Here are three such paths.

Case 1.

Margie is 35 year old redhead who hails from Wildwood, New Jersey, where she helps her parents run a boardwalk diner. I first met her 7 years ago after she had presented with a seizure. In this case the seizure was precipitated by a GBM. A resection of the tumor followed – the postoperative course was complicated by more seizures, and an arrhythmia that brought me into her orbit. I’m a cardiologist so I didn’t see her again until she returned 7 years later with a surgical wound infection – but with no evidence of cancer recurrence.

Case 2.

Mr. Walker was a 74 year old man with a very sick heart when he presented with difficulty speaking. A retired executive who was used to being loquacious, he had survived a heart attack with the help of a stent a decade prior, but had been left with disease in little vessels that gave him occasional angina. Otherwise it allowed him to shuttle between his house and his daughter’s house to enjoy his grandchildren. A granddaughter had a wedding in a few months he was hoping to attend. The question to me related to his cardiac risk of surgery. Was there anything that could be done? He was on anti-platelet blood thinners that would have to be stopped to cut into the brain. Would that be ok? I discussed the case with everyone – his eldest son was an orthopedic surgeon, and his daughter was a medical malpractice attorney. I said nothing that they didn’t already know. He was high risk. I quoted a 10% risk of a heart attack or death with the procedure. Mr. Walker wanted to proceed with the proviso that no heroic measures should be undertaken in the case of a complication- in the event of a cardiac arrest, he did not want to be resuscitated.

Five days later, I received a call from the neurointensive care unit. Mr. Walker had been out of surgery for an hour, and his heart rate was low. I was driving to another hospital, but I asked to be sent an electrocardiogram. What I saw made me turn the car around. He was having a heart attack. The stent he had placed some years ago had occluded. He was having mild chest pain and looked uncomfortable. Taking him for an urgent cardiac intervention was out of the question. This would require not one but four potent blood thinners – almost certain disaster in a man hours removed from major brain surgery. Of even more immediate concern was his heart rate. It was dipping dangerously low – he had developed heart block – a condition where the upper chambers of the heart don’t communicate with the lower chambers. This disconnect is at times reversible, but other times not. As his block worsened, there were seconds that would pass with no heart beat at all. With his daughter at his bedside, I tried to explain what was happening, as I tried to figure out what to do. After a particularly long pause in his heart rate when he passed out, he made it easy – he told me – “I’m not ready to die today”. We placed him on a breathing machine. It took me twenty minutes to thread a wire hooked up to an external pacing box into his heart. As the wire passed through the upper chambers of his heart, it precipitated a rapid arrhythmia. Diseased conduction tissue conducts even slower when asked to work harder, and the fast impulses from the upper chambers caused a heart rate too slow to effectively perfuse his brain. He coded. The wire in his heart wasn’t going where it needed to, and I asked the team to start chest compressions. A long minute later, wire situated, rhythm restored, I walked out to talk to his daughter who had been observing the events outside. She wasn’t happy. She demanded to know what I was doing. I explained the best I could – he was completely dependent on his pacemaker, intubated and sedated. I didn’t think he had suffered any significant brain damage from the recent events, but I wasn’t sure how his heart would do as his heart attack completed. We decided to see how he did overnight and make a decision in the morning.

The next morning I walked into a cheerful Mr. Walker eating scrambled eggs, wire still in place, still pacing him. What else was there to do? I explained to Mr. Walker that without his pacemaker he would die – the next day the electrophysiology team placed a permanent pacemaker, and weeks later, a still cheerful Mr. Walker walked into my office with his daughter.

He made his granddaughter’s wedding, but six months later his brain tumor recurred. He died quietly at home a week later.

Case 3

Frank was a large burly 64 year old, accompanied by his wife, wearing a faded Harley Davidson jean jacket adorned with a a bald eagle and an American flag. He was another man with a cardiac stent heading into surgery for a GBM. As happens frequently, he asked me as I started to finish up with him if I knew the surgeon and anything about the surgery. As I shook his hand, I assured him he was in good hands with the surgical team. He held my hand a little longer and told me that he wanted the best treatment, but he didn’t “want to be hooked up to no machines if there was no hope”. His resection was uneventful, but a week later he returned to the hospital. His wife kept a constant vigil as his clinical state worsened. He had not responded to any commands in days, and a ventilator was breathing for him. The surgeons and the intensivists told me that his wife would not let him go and wanted everything possible done. But there was nothing to do. I couldn’t understand it. His wife had witnessed our conversation. I don’t ordinarily discuss goals of care in patients with non cardiac diagnoses. But I felt compelled to advocate for Frank. I gently reminded his wife of our conversation in the office. She remembered. An awkward silence followed, and I slipped up. I asked her how she could do this. I regretted the words the moment they left my mouth. Her eyes took up the flat look of someone being attacked. I clumsily made my exit, and heard later of her displeasure with my conversation. I never saw Frank again. He died a week later, 4 weeks after I shook his hand in my office.

The population health brigade would have us ignore the messages each patient has to give us. But there is so much here that each patient taught me. Margie reminded me that median survival isn’t destiny. Mr. Walker made me appreciate the fog of decision- making in the terminally ill patient. It is hard to let go of life. Mr. Walker wanted to live on that day. Much of the dollars spent on health care in America are decried as wasteful and I imagine that on paper the dollars spent in the last months of Mr. Walker’s life exemplify waste to some. Yet, you’ll understand how some may see not defeat, but victory in the image of a proud grandfather at his granddaughter’s wedding. Frank’s story is a tough reminder of what I see all too frequently in a world where patient and family autonomy is sacrosanct – moribund patients kept alive by families that can’t let go. There is a fundamental tension between paternalism and autonomy – go to far in either direction and you end up lost.

There is something insidious about those who take issue with terms like battling, fighting and hope in these patients. There is a deeply nihilistic message that lies at the core. You are going to lose – so why fight? Why endure brain surgery, or the radiation or chemotherapy to come? The barbarians at the city gates in healthcare are those who believe the primary role for doctors in this unlucky group of patients is to ferry patients gently into that good night. Baloney. Some patients will choose to fight because they want the opportunity to make that next wedding, others will choose to go home. These are hard decisions best left to the patients and their physicians. You’ll excuse me if I don’t begrudge those wishing the Senator well in what ever path he chooses. Give ’em hell, Senator.

Anish Koka is a cardiologist in Philadelphia. Follow him on twitter @anish_koka