According to recent Ohio statistics, 1.3 million people have limited or no access to primary care physicians. Based on the 2015 Ohio Primary Care Assessment, 60 of 88 Ohio counties have medically-underserved populations. The Patient Access Expansion Act (HB 273), co-sponsored by Representative Theresa Gavarone (3rd District) and Representative Terry Johnson (90th District), specifically addresses healthcare access by prohibiting physicians from being required to comply with maintenance of certification (MOC) as a condition to obtain licensure, reimbursement for work, employment, or admitting privileges at a hospital or other facility.

Recently, I spoke with Representative Gavarone on the critical importance of this legislation for Ohio. Physician family members have grumbled about the expense of MOC compliance however, a practicing cardiologist better clarified the connection between MOC regulations and the growing physician shortage. “He shared his frustrations at the time and money involved participating in a program that has absolutely no scientifically-proven benefit for patient outcomes,” said Representative Gavarone. The cardiologist discussed numerous hours wasted preparing for an exam with little to no bearing on his day-to-day work serving his patients.

While the public may not be familiar with the harm of MOC regulations, many have experience searching for a new physician when their doctor retires earlier than anticipated. “Patients are waiting months for appointments,” said Representative Gavarone. “As physicians leave their practices through cutting back or early retirement, this translates to reduced access to care for everyday Ohio citizens,” she said. Gavarone is touching on a vital issue facing practicing physicians across the country: there are fewer incentives for compassionate, brilliant minds to enter the field of medicine.

Oklahoma was the first state to enact Anti-MOC legislation and six more states (Georgia, Maryland, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas) have passed laws prohibiting the use of MOC as a condition for obtaining medical licensure and hospital admitting privileges. Doctors are being “boarded to death”. To become licensed to practice medicine in the U.S., we must pass 4 exams, each lasting 16 hours in duration over 2 days. The US Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) has three parts: USMLE Step 1 and 2 are taken during our second year and fourth years of medical school, and Step 3 is taken over a two-day “vacation” during internship year.

After a 3-5 year residency program, we must pass a specialty-specific board exam, such as internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery to become licensed. While drowning in more than $100,000 in educational debt, the $1500 exam fee seemed exorbitant, yet passing the pediatric certification exam was only a one-time requirement. States already mandated completion of Continuing Medical Education (CME) hours annually for physician licensure, so why were additional requirements necessary?

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) eliminated “lifetime” certification to shore up their financial outlook; a modification having little to do with quality and much to do with rate of return. Between 2003 and 2013, the ABMS member boards’ assets ballooned from $237 million to a staggering $635 million, an annual growth rate of 10.4%. MOC is outrageously lucrative. Almost 88% of their revenue came from certification fees.

The testing environments to which physicians are subjected are abominable; those who are disabled, ill, pregnant, or nursing find their requests for accommodations in accordance with federal ADA guidelines denied, having no recourse for blatant discrimination. MOC requirements violate our basic right-to-work, an intrusion deemed intolerable in other professions.

Groups lobbying heavily against anti-MOC legislation will likely be hospitals, insurance companies, and specialty groups, such as the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) and Ohio Valley Society of Plastic Surgeons (OVSPS), who are out of touch with front line physicians. Both organizations vehemently opposed a tax on elective (read: unnecessary) procedures projected to add $25 million to the state budget, calling it “discriminatory, economically damaging, and fiscally unsound.” They oppose HB 273 on the grounds that allowing board certification to “lapse” will prevent patients from receiving the “highest quality of care;” a statement that is altogether unproven, misleading, and deceitful.

If you like your doctor, support HB273 –the Patient Access Expansion Act so you can keep them. The MOC program forces physicians to spend time away from our patients, clinics, and families for no demonstrable benefit. Financial corruption touches every facet of MOC; the American Board of Medical Specialties has $701 million reasons to oppose this bill. Representatives Gavarone and Johnson are David bravely battling Goliath. Physicians and patients must help them fight for high-quality, affordable healthcare to be delivered by physicians free of futile testing regulations.

Niran Al-Agba, MD is a pediatrician in Washington State.

When four physician certification boards

When four physician certification boards

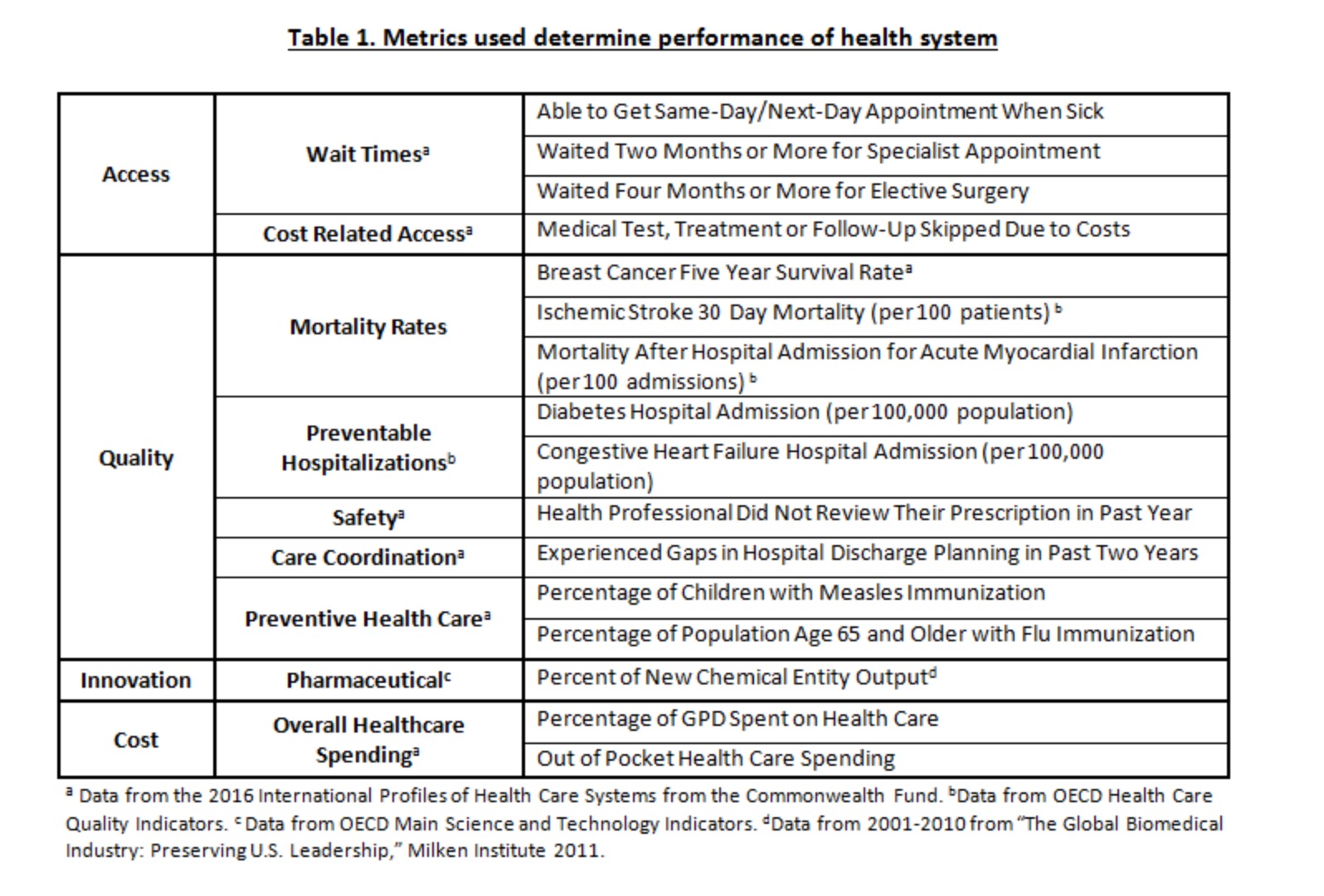

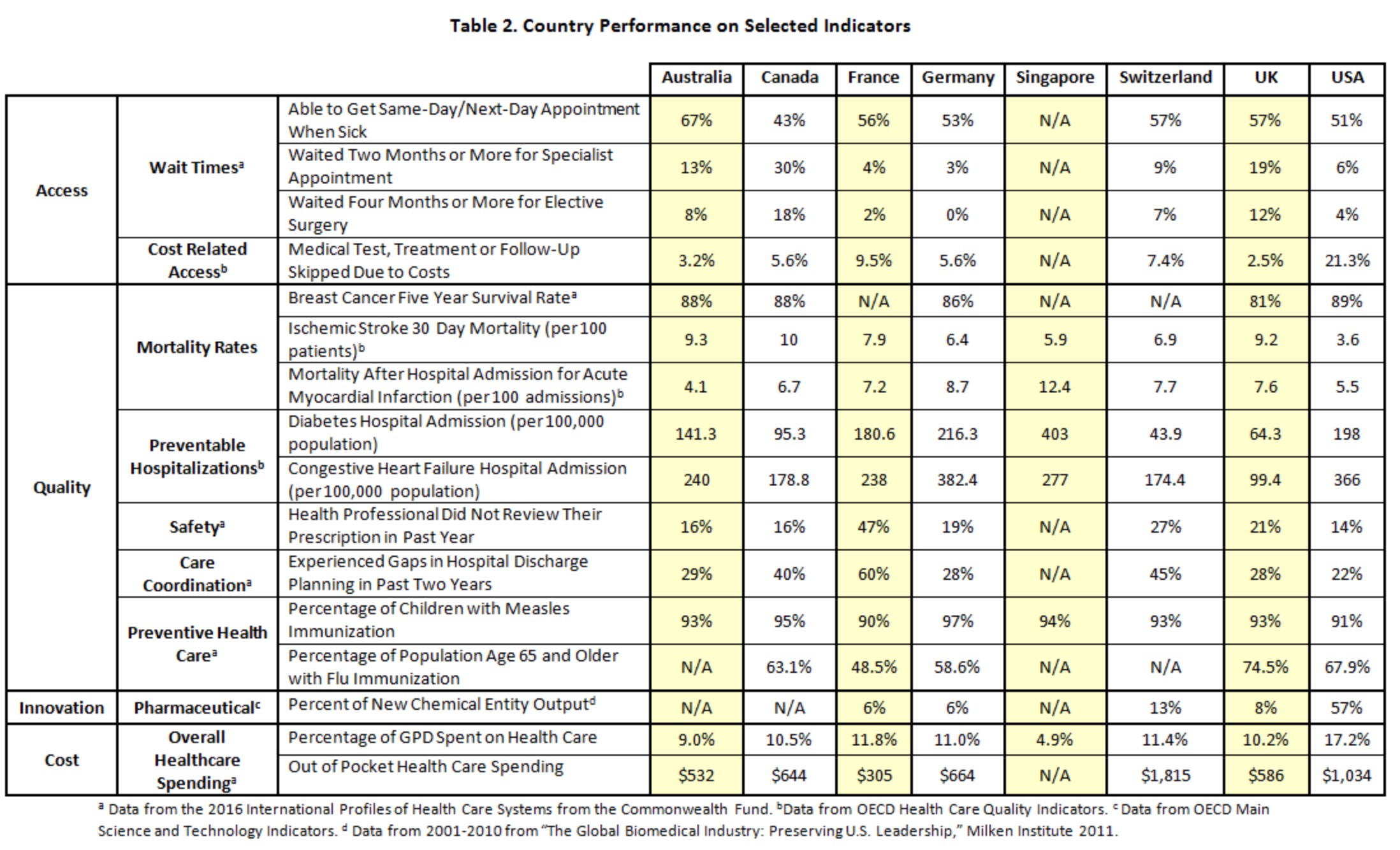

Austin Frakt and Aaron Carroll recently approached me about a New York Times UpShot piece aiming to rank eight healthcare systems they had chosen: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Singapore, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. This forced me to think about a pretty fundamental question: what do we want from a healthcare system?

Austin Frakt and Aaron Carroll recently approached me about a New York Times UpShot piece aiming to rank eight healthcare systems they had chosen: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Singapore, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. This forced me to think about a pretty fundamental question: what do we want from a healthcare system?

Our day-to-day interactions with technology are changing expectations and aspirations for almost every touch point in modern life. We want instant feedback and action at the push of a button, from the digital shopping cart to the doctor’s office. That is part of why there is a constant stream of new apps and tech services being released across every industry, including wellness. But the barrage of options can be a problem of its own nature.

Our day-to-day interactions with technology are changing expectations and aspirations for almost every touch point in modern life. We want instant feedback and action at the push of a button, from the digital shopping cart to the doctor’s office. That is part of why there is a constant stream of new apps and tech services being released across every industry, including wellness. But the barrage of options can be a problem of its own nature.

Last week, the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee wrapped up hearings focused on stabilizing the individual insurance market leaving unresolved an issue that separates Dem’s and Rep’s on the committee: just how much freedom states should have in managing their insurance markets. At issue are the Section 1332 waivers which allow states to reduce essential benefits in health insurance policies, thus allowing insurers to sell policies that cover less with lower premiums.

Last week, the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee wrapped up hearings focused on stabilizing the individual insurance market leaving unresolved an issue that separates Dem’s and Rep’s on the committee: just how much freedom states should have in managing their insurance markets. At issue are the Section 1332 waivers which allow states to reduce essential benefits in health insurance policies, thus allowing insurers to sell policies that cover less with lower premiums.

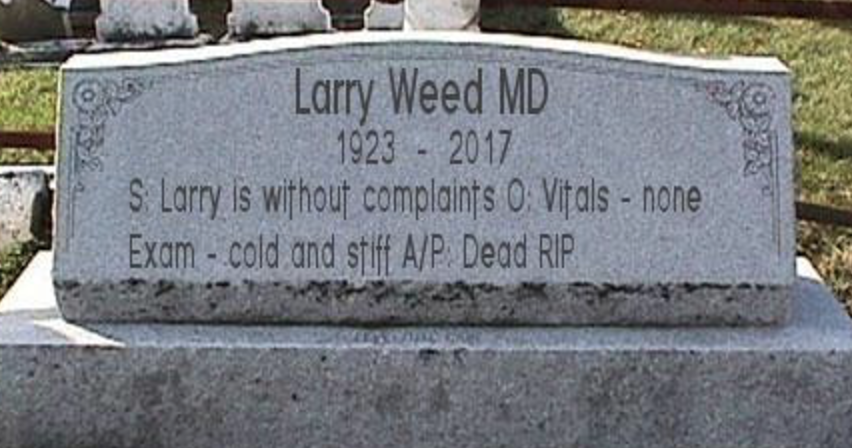

In an age where big data is king and doctors are urged to treat populations, the journey of one man still has much to tell us. This is a tale of a man named Joe.

In an age where big data is king and doctors are urged to treat populations, the journey of one man still has much to tell us. This is a tale of a man named Joe.