By SAURABH JHA, MD

An old disagreement between Uwe Reinhardt and Sally Pipes in Forbes is a teachable moment. There’s a dearth of confrontational debates in health policy and education is worse off for it.

An old disagreement between Uwe Reinhardt and Sally Pipes in Forbes is a teachable moment. There’s a dearth of confrontational debates in health policy and education is worse off for it.

Crux of the issue is the more efficient system: employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) or Medicaid. Sally Pipes, president of the market-leaning Pacific Research Institute, believes it is ESI. Employers spend 60% less than the government, per person: $3,430 versus $9,130, per person (according to the American Health Policy Institute). Seems like a no brainer.

Pipes credits “consumerist and market-friendly approaches to health insurance” for the efficiencies. She blames “fraud,” “improper payment,” and “waste” for problems in government-run components of health care.

But Uwe Reinhardt, economist at Princeton, counters that Medicaid appears inefficient because of the risk composition of its enrollees. Put simply, Medicaid recipients are sicker. Sicker patients use more health care resources. Econ 101.

The points of tension in their disagreement are instructive.

Is ESI free market?

The term “consumerist” instinctively appeals to competition and choice, elements we value in free market. However, health care can’t be compared to shopping for single malt in airport duty free, deciding between Talisker 18 and Glenlivet 21.

ESI is hardly an assortment of private units functioning autonomously and competing with each other. ESI has been carved by so many regulations that the government figuratively runs through its veins.

Do you wonder why insurers in ESI don’t surcharge a family with a child with Tetralogy of Fallot? That is increase their premiums astronomically or deny coverage because of a pre-existing condition.

Goodness of heart? No, it’s because of the government.

This means that young fit joggers are subsidizing the costs for the unfortunate child’s complex cardiac surgery. Insurance is redistribution.

Risk adjustment: Comparing apples and oranges

Failure to adjust for comorbidities makes it difficult to make comparisons in quality, value and performance.

Not only are Medicaid enrollees sicker, they are poorer and less empowered. A priori they are a more inefficient group to deal with than the employed middle class.

I’ll hazard a guess that Sovaldi (medication for hepatitis C) won’t increase Microsoft’s health care bill as much as the state of Illinois’. One, of course, would not credit Microsoft’s cost savings to greater efficiency through clever free market insurance design.

However, in policy discussions comparisons between apples and oranges are commonplace. Life expectancy and infant mortality are used to compare U.S. health care to countries such as Cuba or France, when adjudicators well know, or should know, that there is more nuance. Using metrics which can be affected by social determinants of health is misleading.

Is Medicaid an island?

There are no islands in health care.

It’s important not to make the same logical errors with Medicaid as with ESI. Medicaid is not an autonomous government unit. Its recipients aren’t sent solely to safety net hospitals. For most parts Medicaid recipients share the same system as folks on ESI; a system which, arguably, has been sculpted by ESI, for better or worse.

This means there’s interdependence between ESI and Medicaid, or between a government-regulated/ government-subsidized system and a government-regulated/ government-funded system.

Interdependence would be suggested by cost shifting, where costs of seeing Medicaid patients are shifted to ESI. Even if there is no convincing evidence of cost shifting, as Reinhardt cautions but Pipes disagrees with the caution, this interdependence is not diminished. Providers, or hospitals, might happily see Medicaid patients knowing they can still enjoy good returns from ESI, without purposely shifting costs to ESI, or other forms of insurance.

Politics, Ideology and Medicaid

Medicaid is more than a system of reimbursing physicians. It has become an ideology. Any criticism of Medicaid leads to the unfortunate conclusion by some well-intentioned individuals that the purpose of critique is to send the poor to workhouses and let them die – de facto eugenics. No rational discussion can be had when people shout “Republican reforms kill.” The mob clouded the judgment of Pontius Pilate – and that was before Twitter.

Good intention does not mean access, though. Medicaid recipients have a problem of access. This is because Medicaid pays providers far too little whilst simultaneously imposing far too much red tape. Poor access is fiercely countered by some policy analysts and their fierce counter is fiercely countered by practicing doctors who actually see patients on Medicaid.

Regardless, paying providers the least when caring for the sickest, poorest and most disenfranchised section of society does no favors to that section of society.

Medicaid pays a cardiologist, with years of training, $25-40 for a consultation to manage a complex patient with multiple comorbidities, on polypharmacy, where the cardiologist must indulge in shared decision making and also ensure the patient adheres to statins.

For comparison, my personal trainer charges me $80. There’s no shared decision making – he tells me to do “burpees” and I must abide or face his wrath.

Serve and volley at the margins

Both Reinhardt and Pipes cite several studies supporting their point of view. One wonders whether policy wonks truly can form opinions solely from evidence since it’s so easy to cite evidence to support one’s prior convictions and subconsciously disregard or criticize the methodology of studies which refute our convictions.

For example, outcomes are often used to adjudicate the efficacy of treatments and healthcare systems, and the same constituency which flags poor outcomes when comparing the US healthcare to Sweden’s asks that these outcomes not be used to assess the efficacy of Medicaid. I agree with them as strongly as I disagreed with their use of life expectancy to judge American healthcare.

Disagreements are common because economics is not a hard science such as physics. It does not so much get us to the objective truth as it does to the action at the margins through methodology that is not as robust as the physical sciences, yielding different results on different occasions.

Who is correct, Reinhardt or Pipes?

In a sense both.

Reinhardt is right. Medicaid recipients are not the same as those enjoying ESI.

Pipes is right. Medicaid has structural issues. It pays physicians too little compared to ESI.

This begs the question which reimbursement corresponds to the fair market price in health care: Medicaid or ESI. We will never know because health care has not operated as a free market, and never will. And ESI does distort the price signals as do mandates and virtually everything else.

But here is the important point: ESI is going nowhere. Neither the most left-leaning Democrat nor the most right-leaning Republican has the courage to rid health care of ESI.

What’s the objective truth? Which system really is more efficient?

The truth lies in the answer to this: Would ESI deliver the level of care enjoyed by ESI recipients with paucity of cost sharing that Medicaid recipients face to Medicaid enrollees at a lower cost than Medicaid?

For Medicaid recipients cost sharing should be zero otherwise it defeats the purpose of a safety net. But remember we want them to have the same level of care as ESI for a true apples-apples comparison.

It’s practically impossible to conduct a randomized controlled trial to answer this question. Nor does empiricism suffice. All quantitative analyses have assumptions. With regards to assumptions I can do no better than paraphrase Groucho Marx: “Those are my assumptions, and if you don’t like them … well I have others.”

Importance of disagreements

The current system does not have many genuine alternatives. Single-payer is out as is a genuine free market. As politicians don’t wish to talk about costs because of political expediency, all we are arguing about is which part of health care has the most administrative cost/ informational loss. This is at best a marginal argument. To resolve this argument I would encourage more dialectic between partial truths.

But if Medicaid truly is a high risk pool, and I believe it is, then it should be treated as the other high risk pool – Medicare. Which means that the poor and sick, the uninsurable, should be covered by the Federal government through general taxation. I would suggest a “Medicare for the Poor” which offers the same benefits as traditional Medicare. This would allow the states to balance their budgets better and concentrate on local infrastructure, such as parks, police and public libraries.

Summary of key points

- It’s more cost-efficient treating healthier patients.

- Accurate adjustment for comorbidities and social determinants of health is key for any comparisons in health care. This is (never) seldom achieved.

- There’s interdependence between employer-sponsored insurance and Medicaid.

- No one knows true market prices in health care because it’s not a free market.

- Economic analysis yields information about the margins, until the next analysis.

- The poor should be covered by the Federal government through general taxation.

About the Author:

Saurabh Jha is a contributing editor to THCB. He can be reached on Twitter @RogueRad

Taking home first place, with a grand prize of $50,000, is (drumroll please) Stroll Health (@StrollHealth). Also a previous winner of Traction 2016, Stroll has built a seamless web platform that enables health providers to send patients directly to local imaging centers and specialists, and helps to manage prescriptions. Stroll’s easy-to-use platform provides automatic referrals, prior authorization and real-time scheduling. For the challenge, Stroll expanded their platform to include hundreds of thousands of specialists and more than five thousand prescriptions across the nation. Let Matt and Jordan walk you through the platform themselves in this video.

Taking home first place, with a grand prize of $50,000, is (drumroll please) Stroll Health (@StrollHealth). Also a previous winner of Traction 2016, Stroll has built a seamless web platform that enables health providers to send patients directly to local imaging centers and specialists, and helps to manage prescriptions. Stroll’s easy-to-use platform provides automatic referrals, prior authorization and real-time scheduling. For the challenge, Stroll expanded their platform to include hundreds of thousands of specialists and more than five thousand prescriptions across the nation. Let Matt and Jordan walk you through the platform themselves in this video.

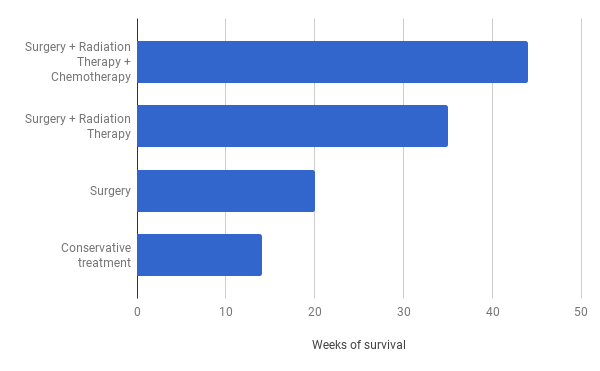

There are 80,000 new cases of primary brain tumors diagnosed every year in the United States. About 26,000 of these cases are of the malignant variety – and John McCain unfortunately joined their ranks last week. In cancer, fate is defined by cell type, and the adage is of particular relevance here.

There are 80,000 new cases of primary brain tumors diagnosed every year in the United States. About 26,000 of these cases are of the malignant variety – and John McCain unfortunately joined their ranks last week. In cancer, fate is defined by cell type, and the adage is of particular relevance here.

I’ve also been having a bit of fun with creating a new site called SMACK.health, which uses the new .health domain extension. Well you knew you needed both a new definition to replace the fuzzy term “digital health” and .com is so 1999! But what am I talking about when I use the term SMACK.health, and why? I was asked to write a piece about technology in health for USA Today spin-off, and I’ve repurposed it here to celebrate the official .health launch.

I’ve also been having a bit of fun with creating a new site called SMACK.health, which uses the new .health domain extension. Well you knew you needed both a new definition to replace the fuzzy term “digital health” and .com is so 1999! But what am I talking about when I use the term SMACK.health, and why? I was asked to write a piece about technology in health for USA Today spin-off, and I’ve repurposed it here to celebrate the official .health launch.

Senators Mike Lee and Jerry Moran said yesterday that they would not vote for the Better Care Reconciliation Act, effectively killing the legislation. As anybody who has been following this story would have predicted, President Trump reacted publicly on Twitter on Tuesday morning, vowing to let the ACA marketplace collapse and then rewrite the plan later.

Senators Mike Lee and Jerry Moran said yesterday that they would not vote for the Better Care Reconciliation Act, effectively killing the legislation. As anybody who has been following this story would have predicted, President Trump reacted publicly on Twitter on Tuesday morning, vowing to let the ACA marketplace collapse and then rewrite the plan later.

The bipartisan 21st Century Cures Act charges HHS / ONC to deal with two issues that previous laws (HIPAA and HITECH) and the Obama HHS left in-progress: information blocking and longitudinal health records. ONC needs to deal with these two issues at a time when there are calls to delay or rescind some Meaningful Use regulations, in an administration that does not favor regulations, with some vendors already starting to ship Meaningful Use Stage 3 EHR products, and while the budget for ONC is still undetermined. ONC can’t be too careful.

The bipartisan 21st Century Cures Act charges HHS / ONC to deal with two issues that previous laws (HIPAA and HITECH) and the Obama HHS left in-progress: information blocking and longitudinal health records. ONC needs to deal with these two issues at a time when there are calls to delay or rescind some Meaningful Use regulations, in an administration that does not favor regulations, with some vendors already starting to ship Meaningful Use Stage 3 EHR products, and while the budget for ONC is still undetermined. ONC can’t be too careful.

An old disagreement between Uwe Reinhardt and Sally Pipes in Forbes is a teachable moment. There’s a dearth of confrontational debates in health policy and education is worse off for it.

An old disagreement between Uwe Reinhardt and Sally Pipes in Forbes is a teachable moment. There’s a dearth of confrontational debates in health policy and education is worse off for it.