I’m a radiologist. I spend my day looking at CT scans and MRI scans. When it’s a good day, I have interesting scans to review, but much of my work is not too dissimilar from a TSA screener’s. One normal scan after the next, it’s akin to trying to stay alert so that the gun someone’s trying to sneak through in their luggage isn’t missed. In my case, of course, it’s a cancer or other unexpected medical abnormality finding.

Computer-Assisted Diagnosis

Most of my day I work on a computer workstation presenting the exams. In my dream, my workstation does more than simply display the exam. It assists in reading the case. If there’s an abnormality, I can click on the area, and the workstation takes the image and compares it to millions of other cases in the cloud. It tells me, based on that patient’s age and sex and other information, how likely it is the finding is a tumor and maybe even, if so, what kind of tumor. At other times the workstation tells me whether a study is normal or not, freeing me to do other activities. However, this dream is not shared by all of my colleagues.

When I mentioned this work-flow scenario to one of my residents—this idea of computer-assisted diagnosis with constant improvement, or what is known as artificial intelligence, or AI—he said it sounded awesome, but he really didn’t want to have it if it was available to everyone. His comment is something of a mixed message: Yes, I see value but no, I don’t want it.

It’s largely based on fear of being replaced by computers. And it’s a song I’ve heard before.

The Transition from Film to Digital

Back in the late 90s, I replaced my camera with a digital camera. I’ve included an early digital picture of my then 4-year-old tearing up, thinking that his Christmas gift was a book. His older brother and sister of course realized that the book was a guidebook to Disneyland and the gift was a trip. To provide some perspective, my son turned 21 last month.

At the same time I was replacing my film-based camera, radiology—my field—was transitioning from film to computers. I started my residency in the same way that my father started his residency in the 1960s. Radiology looked a lot like what we see on TV: lots and lots of films everywhere hung on view boxes to be reviewed. However, by the end of my fellowship, about 6 years later, much of my work was on computers.

I remember at the time of this transition many radiologists had to be dragged into this change. A mentor of mine, Dr. Evan Fram, told me about giving a talk at a university program on how the digital revolution for radiology was really a game-changer. When one of the radiologists in the audience realized that computers would allow fewer radiologists to read the same number of cases, he stood up and said, well, I don’t want this technology then; you’re basically going to eliminate me or somebody else in this room. And Dr. Fram said calmly, look, I’m not the only game in town. This technology’s coming, and we really have to figure out how you’re going to integrate it into your practice. There’s no stopping this now.

Now, 20 years later, I couldn’t practice without computers. The case numbers have exploded in terms of volume and complexity. An average CT that was 40 pictures at the start of my residency might be 2000 images now. And we can do things manipulating those images we couldn’t dream of back in the 90s.

Community and Value in the Digital Age of Radiology

With AI I expect the same level of change over the next 10-20 years. Where the transition from film to digital has allowed radiologists to read more complex cases and a higher number of cases/day, the new technology will increase our value with better diagnoses. The focus will be on the difficult cases rather than on the high volume of normal cases. If AI can help me make a diagnosis that I can’t see with the naked eye—say, for instance, how the brain volume’s changing over months, or how a patient with MS is changing, or insights, perhaps, into a particular tumor that will improve my differential—I’m all for it.

However, there has been a dark side to this innovation. Before, when we were all on film, I used to see my colleagues. They would come to the department; doctors would discuss the patient together; and I would get an opportunity to hear about all sorts of information that today I’m not privy to. Today, I’m much more of a replaceable commodity. My job is not the same job I started with in the 1990’s. And frankly, the radiology community is struggling with this change, with how they work with their colleagues and figure out how to add value in the digital age.

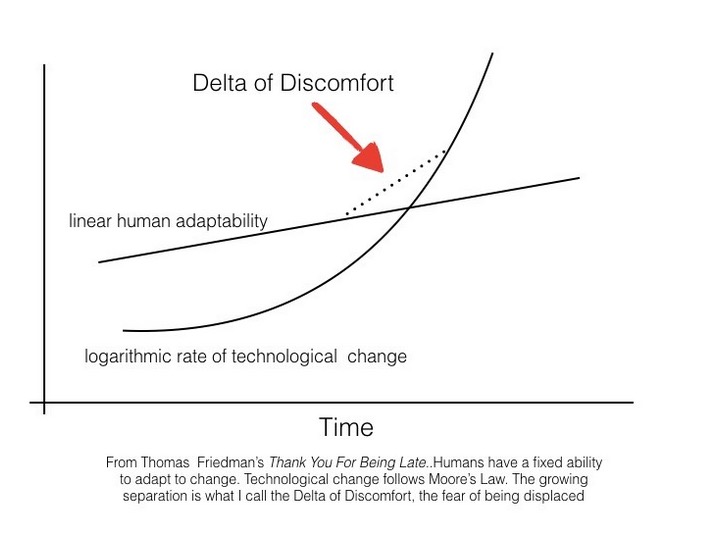

The future of artificial intelligence will be the same—a mix of improved tools but a disruption in who we are as professionals. In his book, Thank You for Being Late, Thomas Friedman has outlined this mismatch, where the speed of technical innovation has outstripped our ability to change with it. There are folks like my resident who fear the future and see only the need for fewer radiologists. The fact of the matter is, however, that the business of healthcare—better diagnosis at a lower cost—will drive this transition. And for me, as with the previous transition, I—or more likely my daughter’s generation—can choose to resist the change and essentially get annihilated by the wave, or try and ride on top of it, directing how the change is applied to our profession and our patients.

Ultimately, healthcare is not for the benefit of the physician but rather for the benefit of the patient. Freed from many of the normal cases I read today, the future radiologist will have to find other ways to add value, likely helping to develop new computer algorithms, further adding to care. They might even have more time to talk to other doctors and patients about what’s really wrong with the patient.

I still think we’re a ways from HAL, the computer in the movie 2001, delivering bad news or even giving a treatment plan to patients. In the words of Mark Twain, “The reports of my death”—or in this case, the death of radiology—”have been greatly exaggerated.” However, this is another song I know. Radiologists in the future will, like the generation before them in adapting to digital reading, have to adopt the new tools of assisted diagnosis. This is in the interest of their patients as well as their profession.